Ganira Ibrahimova, University of Siegen

Abstract

Institutional economics, and in particular the topic of „institutions – entrepreneurship – economic growth“ is very trendy these days. The basic idea behind it is that institutions can shape the conditions for entrepreneurship development or destroy it, and therefore I (institution) is included as a third variable in the relationship between E (entrepreneurship) and EG (economic growth). The purpose of this blog entry is to show how institutions and the behavior of economic agents are related. It provides a basic understanding of the very definition of institutions, their classification (formal and informal institutions), and then demonstrates the impact of institutions on economic behavior in the context of entrepreneurship through various case study analyses.

Introduction

For a long time, standard economic theory has ignored the real processes which influence the actions and decisions of economic agents. The steadily growing interest in economic science nowadays has been focused on the institutional structure of society. Why are the contemporary economists interested in the institutions regulating the exchange processes of the society? To be precise, economics is a science that studies the way a society with limited resources decides what, how and for whom to produce. These processes are very often regulated by market mechanisms. However, the question whether these market mechanisms (supply, demand and market equilibrium point – price) are able to provide the effective functioning of the economic system as a whole, is still relevant.

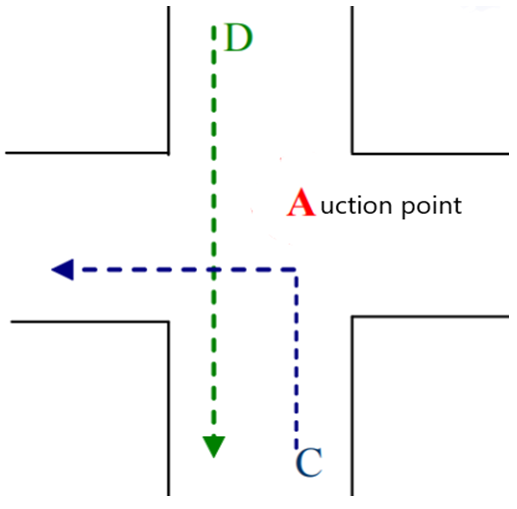

Let us imagine the following situation. The driver C and D approach the intersection at the same moment. They both are in a hurry.

Driver C wants to turn left and driver D wants to go straight ahead. In the situation described, these players need some kind of mechanism that coordinates their actions in a certain way and does not require any excessive organizational cost. What should this mechanism look like?

From an economic point of view, we must apply the laws of supply and demand. To do this, let us imagine a person standing in the middle of an intersection (Point A) announcing an auction for the right to drive first. He accepts price bids from both drivers and will sell this right to the driver, who offers the highest price. The auction continues and price of bids rise until one of the drivers gives up and the other one wins and pays the price for the right to drive first. But as a result – both drivers missed their destination. It is obvious that in this case market mechanism is neither free nor effective.

Do we have any other options? Of course, we do have an institution called ‚Traffic laws‘, which is free and effective. This example demonstrates to us that in many cases market mechanisms are not free, but, on the contrary, they are expensive and not effective at all. Therefore, in some situations, institutions are much more effective tools for coordinating individuals‘ activities (Odintsova, 2014).

Back to the roots – what is an institution?

The first scientist to define the institution was Douglass North. According to his definition, institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, habits, traditions and behavioral codes) and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights). Throughout history, people have created institutions to secure order and reduce uncertainty in interaction processes. Along with the standard economic constraints, they also define choice sets and thus determine transaction and production costs, profitability and feasibility of engaging in different economic activities (North, 1991).

Following the North definition, institutions could be both formal and informal. What do we mean by distinguishing between formal and informal institutions? In the case of formal institutions, we are not only dealing with codified rules, but also with well-organized sanctions. When we talk about informal institutions, on the contrary, we are referring to institutions where the rules are not codified, nor the sanctions. In most cases, the informal institutions are inherited within the social group, the society. People learn about them through the interactions they make.

Simplified, the life of any entrepreneur or economic agent in society is governed by a certain set of rules. These rules both structure our interaction and create restrictions for us. As soon as a rule emerges, there might be incentives to break it, so the rules are often accompanied by enforcement mechanism for their execution. Therefore, institutions are kind of „Game rules“ that are working in society, as well as organizations and businesses operating in this environment are „Game players“, acting accordingly to these rules. However, these rules could work differently from country to country, since there are different sets of informal institutions, complementary, or contradictory to the formal ones.

Formal and informal Institutions: complementary or contradictory?

Let us take an example from the paper „Corruption, Norms, and Legal Enforcement: Evidence from Diplomatic Parking Tickets“ by Fisman and Miguel (2007). It is about UN parking lots in Manhattan, New York. Parking rules must apply to everyone, – they are the same for every driver. But in real life, if you are a diplomat and own a car with a diplomatic number plates, then you have diplomatic immunity, and therefore – are not subject to punishment for inappropriate or illegal parking.

Fisman and Miguel found out, that when diplomats park, their behaviour is very well correlated with the level of corruption in their countries of origin. It appeared that if diplomats come from a country where corruption level is low, they normally do not violate parking regulations. On the other hand, diplomats who came from countries with a high level of corruption tended to be involved in a significant number of parking violation cases.

As a result – we observe different behavior of diplomats from different countries. Formal rules, which diplomats were used to in their own countries, became informal rules when they moved to the United States. It has happened since sanctions for diplomats were not well organized, so these rules, even if they were informal, worked well for them. In 2002, when the law changed and diplomatic immunity was abolished, the behaviour of diplomats from countries with a high level of corruption changed significantly. They also began to park properly.

Outcome: When formal rules (immunity abolishment) complete informal ones (parking properly) the behaviour of economic agents could be completely changed.

However, the outcome is not always predictable. In some cases, formalization of rules could lead to different results. Let us move to another example from the paper „A fine is a price“ by Gneezy and Rustichini (2000). This paper discusses the data collected by researchers in Israeli kindergartens. It describes an example of how many kindergartens are confronted with the problem that parents always pick up their children too late.

There is a fixed timeframe when parents are obliged to pick up their child from kindergarten. However, statistics reveal that Israel is no exception. Very often parents are late to the check-out, – because of the delay at work, traffic jam or other reasons. The formal mechanism for enforcing parents pick up their children in time was missing. So, the nanny, the teacher, or other kindergarten staff member had to sit and wait for the parents to arrive and pick up the child. The only thing that functioned in this case- was an informal institution of shame. Parents felt uncomfortable with their behaviour as they understood that the staff was waiting for them and they had to arrive on time. Nevertheless, there were still delays.

The administration experimented with several kindergartens and introduced the fines for delays, depending on the extent of the delay. Therefore, if parents were late, they had to pay money that corresponds to the time by which they were late. The idea behind was to reduce delay cases, and, consequently, to increased efficiency of the kindergartens. However, the result was very unexpected. The kindergartens which had adopted this penalty system have faced not a decrease, but an increase in the number of parents who are late. The explanation was that parents were no longer ashamed and accepted the fine was a simple fee for extra time. If they felt uncomfortable before, when their lateness was causing the teachers to wait, and this feeling forced them to hurry, now they knew that they can pay for it.

Outcome: In this case, when formal rules (pay fine – feel free to be late) conflict with informal ones (ashamed of being late) the behaviour of economic agents could be also completely changed.

Do the institutions influence economic performance too?

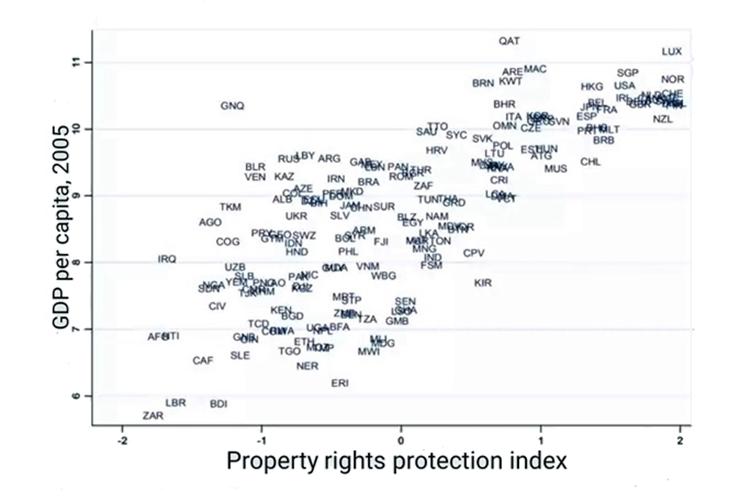

Now, when we become more familiar with institutions, we can analyze how they affect particular business decisions. One of the most important institutions for any business is property rights protection. This institution provides safe investment into physical assets of the companies. While it is generally believed that lawyers, not economists, should be more concerned with property rights, this is not completely true. Very often property rights become the subject of not only legal but also economic analysis. The graph below depicts the index of protection of property rights on the x-axis and GDP per capita on the y-axis. Surprisingly or not, we can see that there is a sort of correlation between these two indices.

It appears that the distribution of property rights and the performance of economic agents are linked to each other and the welfare of society as a whole. The vertical axis represents the GDP per capita for 2005 in a given set of countries. The horizontal axis represents the level of protection of property rights in the same countries. Each point on the graph has been characterized by two corresponding parameters: the index of property rights protection and the GDP per capita in one country. The higher is one index, the higher is the another one. This fact shows us the positive relationship between these two indices. Note that the graph does not indicate that one value is a result of the other, only the correlation is shown.

More case studies, please!

Nepal irrigation case

A very interesting case study can be found in the paper called „Revisiting the Commons: Local lessons, global challenges „(Ostrom, Burger, 1999). This paper is about irrigation systems in Nepal. This country has 28 million inhabitants and most of them employed in agriculture. A significant part of the agricultural land – about 650 thousand hectares, depends on artificial irrigation. This happens because landscape here is very characteristic, and agriculture has to be carried out on mountainous terrain.

Imagine the mountains that are high and steep, having plateaus at different levels. The agricultural fields are located on these plateaus. The landowner of the higher plateau has a better chance of accessing the water since higher lands are situated closer to the water source. The lower the plateau is, the less water could be supplied to the agricultural fields through a given irrigation canal. Moreover, the majority of irrigation systems are not controlled by the state, but by the farmers themselves. The farmers who own upper land and the farmers who own lower land must somehow make an internal agreement about the water distribution and monitoring system. So they have to decide who, when and how will utilize the water, and mutually control that the agreed watering schedule execution is being followed. Besides, the irrigation system itself is quite expensive, so the farmers are also responsible for digging the canals and making sure that it doesn’t get clogged up. But how does the irrigation canal looks like?

In the left photo, we see the old fashioned traditional irrigation system. This canal was dug without the use of modern equipment, and in such a condition, it could easily be clogged up. Operating such a canal involves relatively high transaction costs, which must be shared by all users.

At some point, the state authorities decided to implement a reform under which certain irrigation systems came under government control. In other words, the state began to make considerable investments in the development of these canals: their construction and the regulation of water consumption among farmers. Now the state decided how the water will be used, and under what conditions the distribution of water will take place.

On the right photo, we see a new irrigation system built by the government. It seems to be more advanced than the first one: the canals have been built with the necessary equipment; there is a necessary water drainage system. A more efficient and modern system replaces the traditional one. However, if we look at the comparative effectiveness of the new irrigation systems, we will see that the situation is not so nice at all.

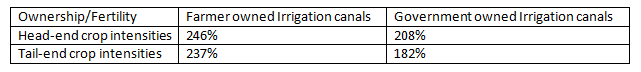

In the table, we see the information on irrigation systems owned by farmers in the left column, and irrigation systems owned by the state in the right column. If the farmer is at the upper end of the irrigation canal, he can get more water than the farmers whose agricultural land is at the lower end of the canal. So, if we want to measure the effectiveness of a particular system, it is not necessary to look at the effectiveness of the system as a whole. We can simply measure the effectiveness in the upper and lower part of the irrigation canal.

How do we measure the effectiveness of the irrigation canal? The soil in Nepal is quite fertile. This means that in one season it is possible to harvest more than one, in some cases even two or three crops. The extent to which a particular soil can be harvested depends on the irrigation. If we accept 100% as the full harvest per year, 200% of the efficiency represents the possibility of having the harvest twice per year, and 300% of efficiency – three harvests per year from a given agricultural land.

This table shows that the simple irrigation systems owned by the farmers were more effective than those modern irrigation systems owned by the State. Indeed, the efficiency was greater when the farmers controlled the irrigation systems and when they felt that it was their common property. The fertility rate in the upper and lower part of the irrigation canal was slightly different, and the overall efficiency was at a level of about 250-240%. However, when the irrigation transferred to State ownership, comparative effectiveness decreased in both the upper and lower parts of the irrigation canal. Thus, if the old private irrigation systems were able to grow about 2.5 full-fledged crops, this amount has now decreased to 2. The government tried to reduce the transaction costs for the farmers and improve irrigation systems, but the result was quite opposite. This happened due to the fact that in private mode farmers were able to decide and organize this process more effective on their own.

Barbed wire case

Another interesting case study is based on the paper „Barbed Wire“ (Hornbeck 2010). In this paper, Richard Hornbeck examines the impact of the barbed wire invention on agriculture and cattle breeding on the great American plains in the 19th century. Indeed, there were fairly well-defined land ownership rights on the great American plains. This means that everyone involved in the interaction – whether a farmer or a cattle rancher – was well aware of their land boundaries. However, this did not eliminate the need to build fences and prevent the cattle grazing on the ranch from crossing the boundaries of the agricultural land and trampling the crops there.

Which material would be suitable for fence construction? The most popular material for fence construction at that time was, of course, wood. But the costs associated with the construction of the wooden fence were very high. What was the explanation for this? First of all, part of the lands was simply quite far away from the forest. Therefore, it was necessary to transport wood for these fences over a long distances, which was costly. At the same time, even if the forest was relatively close to the land, the use of wooden fences was still very expensive, because the wooden fences were rapidly deteriorating. These fences had to be constantly repaired, because the wood was damaged by temperature fluctuations, snow, rainfall, and other natural conditions.

Therefore, when barbed wire was invented, it was a very cost-effective fencing technology compared to wooden fences, and the cost of protecting property rights dropped considerably. Now it was possible not to build an expensive wooden fence, but to use barbed wire, which is relatively cheap and durable in use. Consequently, there was a sharp increase in the outcome of agricultural production. Farmers have diversified their expenditure and grown more expensive and complex cultures on their territory. As a result, the emergence of new technologies had a significant impact on agricultural production development.

„Underestimate me, that will be fun“

Conclusion

Whether we admit it or not, institutions have a great impact on our economic behaviour. Some many more sources and papers show us the relationship between institutions and different economic indices. Even if we consider institutions and entrepreneurship, we will find that they are closely related. The World Bank’s „Doing Business“ report could be direct proof of this statement. This report measures, for example, how registration procedures or taxation (which are formal institutions) might affect the level of entrepreneurial activity in selected countries. It is therefore very important to better understand the role of institutions in the economy and to try to create an effective institutional framework for further and better economic performance.

References

Fisman, R., & Miguel, E. (2007). Corruption, norms, and legal enforcement: Evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. Journal of Political economy, 115(6), 1020-1048, doi 1086/527495.

Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2000). A fine is a price. The Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 1-17, doi 1086/468061.

Hornbeck, R. (2010). Barbed wire: Property rights and agricultural development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 767-810. doi 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.767.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2008). Governance matters VII: aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996-2007. The World Bank. doi 1596/1813-9450-4978.

Lam, W. F., & Ostrom, E. (2010). Analyzing the dynamic complexity of development interventions: lessons from an irrigation experiment in Nepal. Policy Sciences, 43(1), 1-25

doi 10.1007/s11077-009-9082-6.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97-112. doi 10.1257/jep.5.1.97.

Ostrom, E., Burger, J., Field, C. B., Norgaard, R. B., & Policansky, D. (1999). Revisiting the commons: local lessons, global challenges. science, 284(5412), 278-282. doi 10.1126/science.284.5412.278.

Odinstova, M., (2014) „Institutional Economics“ textbook, 12-14, ISBN 978-5759807124.