Abstract

Recent years have seen entrepreneurs and small and medium enterprises play a more significant role in economic growth and cooperation. Economic development increasingly depends on fostering entrepreneurship, where SMEs play a key role in job creation, business development, and stimulating green and inclusive growth in both developing and developed countries. In addition, SMEs are crucial for achieving sustainable development in emerging markets as well. Effective policies and support measures require an understanding of the environment in which entrepreneurs and SMEs operate, referred to as entrepreneurial ecosystem. This blog entry provides a first look at the most popular literature on the entrepreneurial ecosystem, offers different definitions and models of the entrepreneurial ecosystem out of those papers, and provides a comparative case study to see how differently the ecosystem might work even in similar preconditions.

Introduction: What is an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem?

A robust entrepreneurial ecosystem takes decades, as is evident in Silicon Valley, Boston, Tel Aviv, London, Boulder, and Berlin. The growth of such ecosystems can, however, occur anywhere today. The modern economy offers opportunities for every community to be a thriving ecosystem. But what exactly is the “entrepreneurial ecosystem” and why this concept combining economic and biological terms has become so relevant in recent years? As an idea, entrepreneurial ecosystems emerged in the 1980s and 1990s as an alternative to individualistic, personality-based research in entrepreneurship studies. It is no secret that a favorable environment contributes to the rapid development of any form of life. The same is true in economics: the better the starting conditions, the more successful and faster the projects and enterprises are built. That is how the ecosystem concept came to social sciences from biology, to explain the relationship between different kinds of natural elements; therefore, according to this approach, the entrepreneurial ecosystem embraces the networks of business agents and the environment in which they interact. So ecosystem is a spider net, where these players, resources and settings are interacting and related to each other and thus, forming an active and living environment that is either supportive or hindering specific developments (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021 or Sternberg, 2021).

However, entrepreneurial ecosystems have nothing in common with the biological ecosystem while they do not possess the same rationality (Boutillier, 2022); natural ecosystems are resilient to change, returning to a stable state after a shock when the goal of an entrepreneurial ecosystem is to spur growth through the creation of new jobs and the attraction of new financial capital from outside the region (Spiegel, 2020). Besides, as with any system, entrepreneurial ecosystems are interactive and processes with different actors, resources and (institutional) settings, or differently said components, supporting entrepreneurial activity (Van de Ven, 1993), being positive for the region, where the system takes place (Stam, 2015; Stam & Van de Ven, 2021), and in the center of ecosystem, there are entrepreneurs and their profession acting in a kind of setting or the environment promoting or hindering them (Stam, 2015).

Literature review: How it all started?

Looking into the developing research on entrepreneurial ecosystems over time, it is fair to state that ecosystems are a complex phenomenon, consisting of social, economic, cultural, and political as well as individual components within a region or state (Theodoraki & Messeghem, 2017) meaning that they existed throughout the world history. In previous research, they were mostly called “national systems” but it all changed in the 1990s with the James Moore putting forward the notion of a „business ecosystem“, which consists of individual elements growing, dying and coming back to life. Moore (1993): “Entrepreneurial Ecosystem is a space of interconnection and mutual dependence between economic agents, whose collective health was essential for the success and survival of organizations”; this concept includes factors such as structures, relationships between participants, forms of connection and diversities of functions.

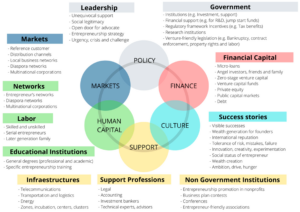

Thus, the enterprise was compared to a biological ecosystem. But James Moore considered only the enterprise level. Later, in 2010, the Harvard Business Review published an article by Professor Daniel Isenberg describing the environment in which entrepreneurship tends to develop. This environment is based on several domains: public policy on SMEs, financial capital, entrepreneurial culture, technical support, human capital and markets. According to this model, all of these six domains are basic and form the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The quality of entrepreneurship in a country depends on the level of its development. In addition, the entrepreneurial ecosystem includes several ecosystems: the startup ecosystem, the venture ecosystem, the university ecosystem, and other elements of the model.

Source: Domains of the entrepreneurship ecosystem, Isenberg, 2010

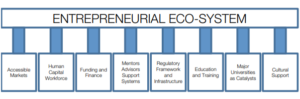

Figure 2: WEF Model

Source: The World Economic Forum report, 2013

Then we have the next big research dealing with ecosystems – a background paper prepared by Mason and Brown in 2014 for the workshop organized by the OECD LEED Programme and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, called Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. The definition they provided in this paper became very popular in ecosystem literature: “The Entrepreneurial Ecosystem is a set of different individuals who can be potential or existing Entrepreneurs, organizations that support Entrepreneurship that can be businesses, venture capitalist, business angels, and banks, as well as institutions like universities, public sector agencies, and the entrepreneurial processes that occur inside the ecosystem such as the business birth rate, the number of high potential growth firms, the serial entrepreneurs and their Entrepreneurial ambition.” It this paper, they did research in several box case studies, using Isenberg domains and trying to develop for the policy-makers special metrics in order to determine the strengths and weaknesses of individual ecosystems so they can be assessed and even estimated in a way. The main contribution of this study was to help policy makers identify whether and how to intervene and monitor over time the effectiveness of such interventions.

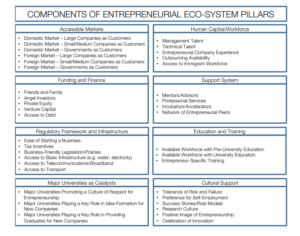

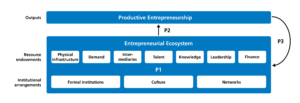

Next big shot in this field belongs to Eric Stam and Andrew Van der Ven and their paper “Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements”, published just recently in 2021. In this paper, they tried to develop a wider model of an ecosystem, including into it more elements and dimensions. Besides, they found causal relationships between the model elements, namely between the P1 section of the model, which is the ecosystem itself, and the model outputs, which is the newly added domain – Productive Entrepreneurship, as you can see in the picture below.

Figure 3: Stam and Van der Ven Ecosystem Model

Source: Stam & Van der Ven, 2021

Table 1: Constructs of entrepreneurial ecosystem elements and outputs

| Concept | Construct | Definition | Element |

| Institutions | Formal institutions | The rules of the games in society | Formal institutions |

| Informal institutions | Cultural context | Culture | |

| Social networks | The social context of actors, especially the degree to which they are socially connected | Networks | |

| Resources | Physical resources | The physical context of actors enables them to meet other actors in physical proximity | Physical Infrastructure |

| Financial resources | The presence of financial means to invest in activities that do not yet deliver financial means | Finance | |

| Leadership | Leadership that provides guidance for, and direction of, collective action | Leadership | |

| Human Capital | The skills, knowledge and experience possessed by individuals | Talent | |

| Knowledge | Investments in (scientific and technological) knowledge creation | Knowledge | |

| Means of

consumption |

The presence of financial means in the population to purchase goods and services | Demand | |

| Producer services | The intermediate service inputs into proprietary functions | Intermediate Service | |

| New Value Creation | Productive entrepreneurship | Any entrepreneurial activity contributes (in)directly to net output of the economy or the capacity to produce additional output | Productive entrepreneurship |

Source: Stam & Van de Ven, 2021

Ecosystem comparison case study: What can the policymakers learn?

As discussed in the paper reviews above, the entrepreneurial ecosystem might appear as a kind of experimental laboratory, where under the influence of various factors (historical, political, natural, resources availability and proportions. a country-specific ecosystem has been created. Similarities and differences in the entrepreneurial system allow us to go for cross-country analysis, such as Azerbaijan and Georgia. When doing a comparison of entrepreneurial ecosystem design, it is necessary to distinguish between the external conditions of business agents and the entrepreneurial environment. SME development is determined by basic conditions; natural resources, economic and geographic location (proximity to markets), innovation potential, infrastructure, cultural and other peculiarities of the region, which cannot be dramatically changed within a few years. The entrepreneurial environment, which determines the access of entrepreneurs to finance and specialized services, the level of administrative pressure, the complexity of business registration, etc., is subject to short-term changes, including those resulting from political decisions. Therefore in our case study, we will illustrate the policy side of ecosystem design showing how differently it works with countries situated in one region and having many commonalities. The countries we choose are Azerbaijan and Georgia, two small countries situated in the South Caucasian region and having a long common past called USSR, and short period of 30 years of independence, which lead to absolutely different entrepreneurial ecosystem settings and outcomes. In Azerbaijan, the government faces the challenge of creating conditions that will facilitate growth in nonoil tradeable sectors, while Georgia has to develop entrepreneurial activity due to the absence of natural resources. The statistics also show the opposite situation, in Azerbaijan more than 90 percent of export belongs to oil sector, while in Georgia 90 percent to private sector contribution. However, natural resource abundance is not the only explanation for such a situation, while there are countries having both sectors developed, like Norway or US. To illustrate these differences in ecosystem settings we will use the data and make a simple SWOT analysis between both countries’ entrepreneurial ecosystem situations, based on SME country data.

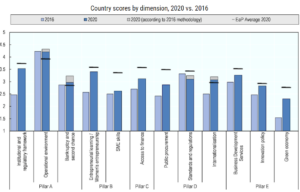

Figure 4: SME Policy index for Azerbaijan

Source: OECD, 2020

Table 2: SWOT analysis of Azerbaijani Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Comparatively good infrastructure and service provision level (BEEPS)

Extensive e-government system Government programs for SME support and promotion (ASAN, ABAD, NTFS) Easy procedures for starting a business Low price of energy Government incentive Simplified taxation for entrepreneurs |

Limited access to bank finance

Low level of competitiveness Low level of innovation and R&D Lack of coordination between state programs supporting SME Lack of public and private business consultants Lack of structured institutional set-up Low level of business skills Low capacity for export and internationalization |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| Strategic Road Maps appliance

Non-oil export program development SME Involvement into public procurement and infrastructure projects Development of human capital Rising the awareness of citizens Creating favorable business climate Creating exchange market mechanism WTO membership |

Foreign impact factors

Weak banking sector Devaluation of manat Poor competitiveness Oil dependence Lack of innovation agencies Territorial conflict Lack of infrastructure in rural areas Absence of stock market culture |

Source: Own research, based on national data

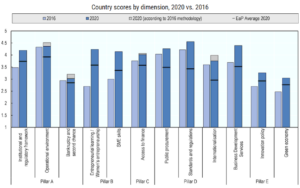

Figre 5: SME Policy Index scores for Georgia

Source: OECD, 2020

Table 3: SWOT analysis of Georgian Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Favorable business environment

Easy procedures for starting a business Advisory and consultancy services for SMEs Corruption free government Low tax burden and preferential tax regime for micro and small businesses Easy and low cost access to regional and international markets Well-developed infrastructure Existence of SMEs supportive institutions Governmental programs for SMEs promotion |

Lack of business skills

Low level of competitiveness and productivity Territorial conflict Limited access to finance in long-term insufficient collaboration between public R&D institutions and SMEs Limited capacities for technology absorption Lack of knowledge on foreign markets Low capacity for export and internationalization High cost for consultancy services for SMEs Difficulties in closing business |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| Increasing access to finance

Developing opportunities for export Improving the quality of infrastructure Decreasing technical barriers to trade Diversification of SMEs internationalization strategies and production Developing advisory and consulting services Increasing innovation capacities and technology absorption potential Establishing modern entrepreneurial culture |

Possible external economic shocks (like financial crisis, or decrease of demand on international markets, etc.)

Possible downturn of economy Low investment in SME sector Insufficient export capabilities Low capabilities of SMEs in terms of international competition Insufficient knowledge about export market requirements |

Source: own research, based on national data

Conclusion

As we see from all the ecosystem literature and models illustrated in our blog entry, entrepreneurial ecosystems are essential parts of the communities to foster entrepreneurial growth, country growth, and self-growth. They help entrepreneurs to find quickly what they need. Besides, regions with well-developed entrepreneurial ecosystems are generally better adapted to external shocks, as they have greater business-agent competition and diversification of activities. However, the case study of two countries such as Azerbaijan and Georgia, with a similar history, size and geography is direct proof that even with the same elements ecosystems might have very different designs. Everything depends not only on the ecosystem elements (they can be identical) but also on the degree to which one particular element affects all the others (such as institutions, for example) and how this interaction changes the whole system outcomes. This impact might improve or destroy the connection between other elements or help to exclude ineffective elements and stimulate the emergence of new and improved ones. This caveat is very important and should stimulate the ability to think for the researchers who use the concept of the ecosystem as a tool or black box, without any critical distance to the concepts they use. In addition, it might help the policymakers to understand social complexity of an ecosystem and give them a hint that a) entrepreneurial ecosystems should be regulated while they are not tending to achieve an optimal state b) there is no one-size-fit ecosystem that could be accepted as a gold standard, rather it is a country, region, and even city-specific setting to achieve. Therefore, it is a directed goal, where policymakers, entrepreneurs, and other ecosystem architects try to intelligently design the entrepreneurial ecosystem to make it the best possible environment for high-growth firms.

References

- Boutillier, S. (2022). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems, Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 37(1), 209-213. DOI 10.3917/jie.037.0209

- Spigel, B. (2020), Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Theory, Practice and Futures, Edward Elgar publishing.

- Isenberg, D. J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard business review, 88(6), 40-50.

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Final report to OECD, Paris, 30(1), 77-102.

- Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harvard business review, 71(3), 75-86.

- OECD et al. (2020), SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union, Brussels, DOI 10.1787/8b45614b-en.

- O’Connor A., Stam E., Sussan F., Audretsch D. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Place-Based Transformations

- and Transitions. NY: Springer, 2018. 197 p.

- Stam, E., & Van de Ven, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, 56:809–832. DOI 10.1007/s11187-019-00270-6

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759-1769. DOI 10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Sternberg, R. (2021). Entrepreneurship and geography—some thoughts about a complex relationship. The Annals of Regional Science. DOI1007/s00168-021-01091-w.

- Strategic Roadmaps for National Economy and Key Sectors of the Economy (2016) https://monitoring.az/assets/upload/files/15075d6928310402cd152c96db0d6835.pdf (online resource).

- The Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic, 2021 (Official request 21st of April, N02/1-202)

- The Statistical Committee of Georgia https://www.geostat.ge

- Theodoraki, C., & Messeghem, K. (2017). Exploring the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the field of entrepreneurial support: a multi-level approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 31(1), 47-66. DOI 10.1504/IJESB.2017.083847

- Van de Ven, H. (1993). The development of an infrastructure for entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(3), 211-230 DOI 10.1016/0883-9026(93)90028-4

- https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_EntrepreneurialEcosystems_Report_2013.pdf (online resource)