Jessica Espinoza, external doctoral student at the Professorship of Business Administration, in particular of SME Management and Entrepreneurship, University of Siegen.

Contact: Jessica.ETrujano@uni-siegen.de

Abstract

The way we allocate capital and invest shapes the world we live in. Investors play a crucial role in deciding which ideas and opportunities get the chance to grow and which remain unexplored. So one of the best ways to drive change at scale is to change the way we allocate capital. Gender lens investing offers investors an exciting opportunity to do that.

SDG 5, Gender Equality, is not only an extremely important goal in and of itself, but also a catalyst to achieve all other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, there is a strong nexus between gender and climate goals: we cannot achieve either without the other. So to unlock the full potential of climate action, all climate finance must be gender smart (here is how). There is a similar nexus between gender equality and peace and security as well as a range of other impact goals.

The business case for investing in women is equally strong: companies founded by women deliver twice as much revenue per dollar invested. Similarly, gender balanced leadership teams in private equity generate a 20 per cent higher net IRR,

Despite growing consensus that it makes business and impact sense to be gender-smart in business and investing, women still hold only eight per cent of all senior positions in venture capital and private equity firms in emerging markets and only 10 per cent in developed markets. And so unsurprisingly, the needle hasn’t moved on the frequently cited 2% of venture capital that goes to female founders.

At the current rate of progress, it will still take 151 years to close the economic gender gap globally, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2022.

Shifting capital with a gender lens

Momentum in gender lens investing is growing rapidly.

Given a strong impact case coupled with a robust business case for investing in gender equality and women’s empowerment, gender lens investing resonates not only with impact investors but also with commercial mainstream investors. The full spectrum of capital providers – including development finance institutions, multilateral and public development banks, pension funds, family offices, commercial banks, insurance companies, private equity, venture capital and debt funds – are today actively engaged in gender lens investing.

Globally 67% of asset owners identify gender diversity as an area of interest within their investment portfolios. Today, an estimated 206 private equity and venture capital funds deploy capital with a gender lens, totaling US$ 5.4 billion in AUM (US$ 13.2 billion targeted by these funds in their ongoing fundraising).

2X investment framework

The 2X Challenge was launched at the G7 Summit 2018 as a bold and joint commitment by development finance institutions with the goal of investing and mobilizing at least US$ 3 billion over 3 years. The original target was significantly overachieved with more than US$ 11.4 billion committed and mobilized by the end of 2020. Remarkably, in the Covid-year 2020, the 2X capital pool grew by almost 170%, demonstrating a solid pipeline of gender-lens opportunities even in times of uncertainty, volatility and crisis. This strong signaling has paved the way for scaling gender lens investing globally and has crowded in a wide spectrum of investors and capital providers.

The 2X investment criteria have quickly become a global industry standard for gender lens investing, enabling investors to focus on opportunities for positive gender outcomes along the value chain. The 2X Criteria focus on 1) companies founded and owned by women, 2) companies with women in senior management and on the board, 3) companies providing quality employment to women and creating gender equitable workplace environments, 4) companies with products and services that enhance the wellbeing and the economic participation of women. For financial intermediaries such as financial institutions and private equity or venture capital funds, the criteria apply both at the level of the institution as well as at the level of its portfolio companies.

Where is gender-smart capital flowing? How? And who decides?

Where is gender-smart capital flowing? Across which asset classes, growth stages, sectors and regions, and under which 2X criteria? These are the key questions we as a field have been asking in recent years to understand what works, where the persistent gaps are and how we unlock untapped opportunities with more intentionality. On 2X’s part, we have been analyzing the 2X Challenge capital pool of over US$ 11.4 Billion and shared a learning report with the broader field.

While the “where” question – where is capital flowing – remains important to ask, there are two other questions which are as important: How is capital flowing? And – my favorite one – who makes those investment decisions?

The question of how capital is flowing focuses on intentionality and processes across the investment cycle. How investments are made, how culture is shaped and how intentionality plays out in practice is largely determined by the question of who is in charge.

Responsible Exits in Gender Lens Investing – Why care about exits?

Over the last months, I have been leading an insightful research project on behalf of the 2X Collaborative in partnership with Investing in Women and with support from DFAT: Developing practitioner-shaped principles for responsible exits in gender lens investing.

Gender lens investors are going the extra mile to build a portfolio of enterprises that create women’s economic empowerment outcomes through women’s representation in business ownership, leadership, among employees and suppliers, as well as through products and services benefitting women. Exits from equity investments in gender-smart funds are relatively recent – giving rise to questions on how these funds can ensure that their women’s empowerment outcomes are preserved and scaled post exits.

To gain deep perspectives and industry practitioner insights, we conducted in-depth interviews with

- women entrepreneurs anywhere in the world who have ideally raised a Series B (and beyond) or have experienced exits through buyback, buyouts, trade sale or IPO, and

- investors, especially fund managers across global markets that have ideally achieved exits from their gender lens portfolio or are proactively working with their investee companies towards a responsible exit aimed at preserving gender outcomes. This included mainstream commercial fund managers who have exited from women-led companies.

The gender lens investing industry has responded to this initiative with significant excitement and a keen interest to tackle these questions around responsible exits from a gender lens perspective which haven’t received much attention so far.

Some have also asked us why it is so important to talk about exits at this stage where the industry is still tackling the question of how we get investors to write more checks to women entrepreneurs in the first place. Put simply, the answer is that you can’t enter responsibly if you haven’t thought about how to exit responsibly. Investors and entrepreneurs alike need to think about responsible exits from the very beginning – even before they sign the deal.

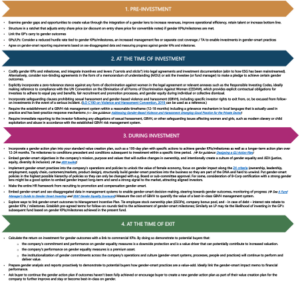

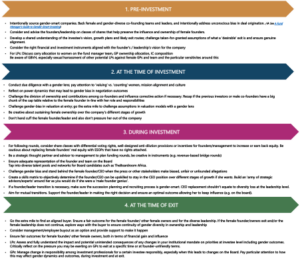

Therefore, the newly developed principles for responsible exits encompass the entire investment cycle and feature actionable guidance at every step of the way – from origination, to due diligence, structuring, portfolio management and value creation, all the way to exit.

Here are the top novel insights from our research and the resulting principles:

Principle 1:

We will ensure that gender is one of the key value driver of the investee company. (internal)

Research Insights:

“What we want to create is a big picture of everything ESG, gender and impact related, and be able to show that it’s an ecosystem that works together, and that if you try and extract one item of that ecosystem, you’re probably going to lose the entire value that you create. If we’re able to show diversity aspects that brought to the company that much in terms of financial return we can have a very different conversation with the new investors.”

– PE GP, Africa

There was overwhelming consensus by investors and entrepreneurs that gender should be incorporated into the core operations of the company and as a key value driver, making a clear business case in addition to the impact case. This is crucial to ensure a strong gender lens is embedded in the DNA of the company and across its value chain so that it is hard to ‘unwind’ it post exit.

Fund managers (GPs) highlighted the importance of embedding gender objectives and milestones in the value creation plan from day one and focusing on achieving them within the first years of the investment. Especially in environments where exits are challenging, an opportunity may arise earlier than expected so it’s important to establish the foundations and create gender-smart impact early on.

In our research, most investors emphasized the importance culture beyond everything else: if a strong gender-smart culture can be built over the investor’s holding period, it is much more unlikely that progress would be rolled back post exit.

For example, GPs pointed out that in an M&A transaction a big success factor is the people component and one of the biggest risks is that people – beyond the top talent, the core group in the middle range – may leave the company. So when gender-smart practices are deeply embedded in the company culture, it may be in the buyer’s best interest to keep them as otherwise employees may leave the company.

In addition to culture, board composition and structure, including committees (such as HR committees with a strong gender-smart approach to HR) were highlighted as crucial structural elements to sustain gender outcomes.

Some GPs actively share the gender analysis they have conducted over the lifetime of the investment with the incoming investors to demonstrate the business case for continuing the gender action plan post transition.

Principle 1 in Action:

-

Incorporate a gender action plan into your standard value creation process

-

Tie gender KPIs/milestones to the performance incentives for investees

Principle 2:

We will stand behind the female founders and the leadership team. (internal)

Research Insights:

GPs observe that in mixed teams, female co-founders often get less equity than their male co-founders even when they have more responsibilities. Some GPs actively step in and challenge the division of ownership and co-founder contribution to ensure the cap table isn’t distorted from the very beginning which is hard to correct later.

We found significant anecdotal evidence that women entrepreneurs not only get fewer funding and smaller tickets but also lower valuations than their male counterparts. Private equity GPs told us by the time a company reaches significant funding rounds for growth capital, the female founder may have already gotten so diluted and replaced as CEO that she no longer plays a significant role in the company. At the Series B and C stage, especially in emerging markets, we also heard the concern from investors that female founders got so diluted in previous rounds that new investors have a hard time coming into the next round, as the founder no longer has significant “skin in the game”, i.e. enough ownership to be appropriately incentivized.

Several GPs with innovative gender lens investing strategies shared actionable guidance on how investors can support female founders and leaders to preserve or regain equity and influence. Differential voting rights, well-designed anti-dilution provisions and incentives for founders/management to earn equity back were highlighted by both investors and founders as useful mechanisms to preserve the influence and ownership of female founders.

While ESOPs were identified as a useful option to incentivize founders, some pointed out key differences between equity versus ESOPs, as an ESOP often does not come with voting rights and control; this is something to pay particular attention to.

Closely related to founder dilution, several GPs highlighted the risk that female founders and leaders could be sidelined or asked to leave with new investors coming in. This is hard to protect legally and so GPs focus largely on making the case why the female leadership is a value driver and crucial to the success of the company.

Similar to the 2018 GIIN report on responsible exits in impact investing, many agreed that management continuity is desirable to preserve the company’s mission, strategic direction, impact and know-how. On the one hand, investors pointed out that a founder’s transition from CEO to another role is an industry norm irrespective of gender, because a different skillset is required at the growth stages.

Women entrepreneurs pointed out a constant gender-biased pressure and risk of being pushed out of the company as they raise equity funding rounds. In their experience, there is a double standard where investors go the extra mile to keep male startup founders in the CEO position based on the taken-for-granted assumption that they are a “genius” and irreplaceable, bringing in a whole “army of strategic advisors” and experts to build expertise around the CEO, whereas female founders are replaced as CEO much earlier.

„Female founders don’t get market terms even if investors say they are GLI. And if they push back because they have good counsel they get classified as ‘difficult’.”

– VC Tech GP

“We invested in her Series A and B. When we were talking to potential investors for the Series B, some VCs instantly wanted to replace the female CEO – and they hadn’t even met her. I think if it was a male CEO founder they would have at least met him before making a judgement. (…) We didn’t bring these investors on board.”

– VC Investor,

Europe & Asia

“Women are asked questions to defend their business, about traction to date and to show proof. When men are fundraising, they’re asked questions about future potential and these questions lead to a larger valuation, because you’re talking about the future, how big things could be. Women are asked about their actual achievements to date and a valuation based on that will always be smaller compared to one based on what you can get in the future. It’s such a huge problem.”

– Female Founder, CA, USA

(Series B stage)

„No one is perfect. But male founders are given the leeway to augment themselves while women founders are expected to be perfect which is impossible. So for a male founder it’s fine to surround him with a team of experts and that’s perfectly acceptable. But for women, I think they’re asked to actually do impossible things. They don’t have the luxury of being able to complete gaps. Male founders are allowed to plug gaps all the time. But for women, the moment the gap appears – and gaps appear in startups all the time – they are asked to be replaced. I mean, as a VC, you’re supposed to help plug the gaps, right?“

– VC Investor, Europe & Asia

Principle 2 in Action:

-

Protect founder’s interest in the cap table, and create diversity in leadership and ownership with intentionality

-

Manage founder/CEO transition responsibly, ensuring fair outcomes for the female founders and the leadership team at exit

Principle 3:

We will challenge gender biases in valuations of the female economy. (external)

Research Insights:

„I’m hit by the double whammy of working in childcare, which is historically undervalued as an industry and seen as women’s work and therefore not valuable. Many investors we’ve spoken to have had trouble grasping the size of the market. It’s a massive market, it is a big deal. But their personal bias is like ‘I think like web 3 is more interesting and sexier’. But even in this space, there have been some companies that have received outsized funding – all founded by men. Most childcare companies are actually founded by women and none of those raise significant amounts of funding. So it’s kind of ridiculous how blatant it is.“

– Female Founder, CA, USA (Series B stage)

Research data and lived experience of our interviewees points to the fact that female founders get only a fraction of capital, smaller tickets and worse valuations due to gender biases. (MassChallenge 2021 , Carta 2018)

Women entrepreneurs highlighted that due to the devaluation of women’s work (e.g. care economy) and needs (e.g. femtech, female hygiene products, fashion and cosmetics, Black women’s hair industry etc.), businesses focused on female economy (which are also predominantly founded by women) tend to get lower valuations. In addition to the recognition that women dominated sectors have long been undervalued, entrepreneurs expressed frustration that investment decision-makers are still predominantly men and don’t understand the market potential of industries like women’s health or the care economy.

Some female investors pointed out that the recognition of the “business case” for gender lens investing does not always go hand in hand with valuing women’s contributions and the female economy. We heard anecdotal evidence of the risk that some may see a “business case” in perpetuating the undervaluation of women. “Players with bad terms and reputation are now branding “gender-lens” thinking women accept bad terms,” a VC tech GP told us.

Further, women entrepreneurs observed that lower initial valuation and higher dilution may mean that the founders’ exit from a company she has successfully grown doesn’t result in wealth creation for herself, perpetuating the cycle of limited industry credibility and capital for women entrepreneurs for their next roles, whether as serial entrepreneur or angel investors.

The media’s role in shaping perceptions was cited particularly by women entrepreneurs who told us they are mostly interviewed about women’s challenges and struggles rather than their potential and successes. The media was also pointed out as playing an important role in fueling the “rise and fall” of women entrepreneurs. Female founders expect gender-smart investors to take a stance and stand behind women leaders in the face of biased accusations.

„Media uses the platform to talk about women as beneficiaries, women as struggling to make ends meet, women needing impact, women needing saviours. And so unfortunately, that rhetoric is not helping our cause. 99% of the time that I’m interviewing with any of these big media brands, the first question they asked is, tell us why it’s so challenging to be a woman entrepreneur. The fact that that’s the phrase that we’re using, and we’re not going ‘women are bad asses, let’s talk about all the reasons why you’ve been successful as a women entrepreneur’.”

– Female Founder, Asia

(Series B stage)

Interview with entrepreneur Aisha Pandor, CEO & Co-Founder of SweepSouth and investor Julia Price, Linea Capital [embedded video]

Principle 3 in Action:

-

Scrutinize gender biases in valuation at entry and at exit, critically assess assumptions in valuation models with a gender lens

-

Advocate fair valuation of businesses in the female economy

Principle 4:

We will ensure buyer’s gender alignment at the time of exit. (external)

Research Insights:

Contractual agreements at exit with provisions requiring the new shareholders to preserve gender outcomes are very rare. Our interviewees shared that even basic ESG requirements are hard to negotiate in contractual agreements with buyers and that it would in any case be hard to enforce in case of non-compliance. This was surprising to us, as the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN)’s principles for responsible exits on impact investing already in 2018 highlighted a multitude of legal structures to preserve impact beyond exit. This would include embedding gender-smart objectives and practices in legal structures, such as bylaws or shareholders agreements, to avoid confusion about strategic direction and priorities.

Instead, our interviewees largely emphasized the importance of establishing a culture with gender equity and DEI at its core which is very hard to change once established. Some GPs are using ‘best efforts’ language about gender-smart objectives in key documents, which don’t have much teeth but signal intentionality.

Some founders we interviewed have successfully included a clause on mission and values alignment in shareholder agreements as well as a clause on the need for an unanimous agreement on exit. Furthermore, some have negotiated clauses that if the responsible person changes at the investor firm, they lose their Board seat and have to reapply for the seat with their proposal for a suitable candidate.

Gender lens investors observed that some gender outcomes may be harder to sustain at exit than others. For example, supplier diversity was cited among the gender-smart practices most at risk of getting dropped when a new shareholder comes in.

Several investors interviewed pointed out that regulation and stock exchange requirements related to gender diversity would help them make the case to buyers for a strong gender lens.

Several respondents were curious about that ‘next step’ of adding gender-smart objectives to legal agreements: How does the market feel about this? How do you practically do this?

Timing of the exit is key and finding the best exit route to preserve gender outcomes may require flexibility on timing. However, this in practice not necessarily at the discretion of GPs who may face pressure from their limited partners (LPs). Exits at a certain point in time are required for the GP to be even in a position to fundraise for the next fund. It is therefore crucial for LPs to be aligned on responsible exits.

„When exit time comes, it doesn’t matter who the impact investor is. Everyone becomes a shark. So I think the only answer is to pick the right investors from day one and truly assess their thesis, because some claim to be a gender lens investors, but they are not necessarily practising that.”

– Female Founder

Asia (Series B stage)

Female founders, too, highlighted the power of LPs, explaining that the dynamics with GPs can something change quite quickly when the GPs are facing pressure from LPs due to mandate changes or new priorities at the LP level. This can have significant influence at the investeee level. Founders who have realized this notonly conduct their own due diligence on GPs but also on the LPs who invest in their funds.

Finding aligned buyers is crucial to sustain gender outcomes. As part of implementing the Operating Principles for Impact Management (OPIM), some GPs are now sharing impact questionnaires with potential buyers to assess mindset alignment. This is a good starting point to incorporate a strong gender lens.

Gender-smart GPs are innovating with new structures to bring on board women as LPs, pooling lower ticket sizes, thereby allowing more women to become investors and contributing to buiding women’s wealth (see for example Linea Capital, Five35, Sweef Capital and Amplifica Capital). Furthermore, some gender-smart GPs have started to explore employee buy-outs as an exit option to preserve women’s ownership and mission-aligned continuity for the company. For practical inspiration, see ‘Adventure Finance’ by Aunnie Patton Power.

„I hope that after post-exit my company will still be women-led and be a force for good. Can we at least keep a majority of women on the cap table? Or at least give them a really good financial outcome so they can use that wealth to back many other successful women-led companies?“

– Female Founder, USA

(Series B stage)

Principle 4 in Action:

-

Seek out buyers who are committed to gender-smart investing and conduct due diligence with gender lens

-

Explore ways to bring women on the cap table and consider management/ employee buyout as an option

Case Study: Adenia Partners

Intentionality in planning for and facilitating management buyout

In 2011, Adenia partnered with Titi Rafidimanana to merge two small family businesses and create Fruid’iles Export the number 7 litchi export station in Madagascar (out of 30+ exporters). She fully managed the operations of Fruid’iles since 2011. Her major achievements include:

- She oversaw the construction of a new export station (1,700 sqm) compliant with international standards for fruits and vegetables

- She managed a team of 7 permanent people and 700 employees during litchi campaigns (harvests)

- She obtained the Global GAP certification in 2012 and Fair Trade in 2013

- In 2015, she was one of the first litchi exporter to implement the Global GAP Risk Assessment on Social Practice (GRASP) which is s a voluntary, farm-level social/labor management tool for global supply chains

- She developed an entire network of partner farmers (total production volume coming from partner farmers increased from 0% in 2011 to 70% in2016)

In 2018, Adenia helped Titi to negotiate and secure a loan which then allowed her to acquire Adenia’s 63% stake in Fruid’iles export.

Based on these novel research insights, we are now developing a toolkit with case studies and good practice examples offering gender lens investors actionable guidance. We welcome your input!