Mark McAdam, University of Siegen

Contact: mark.mcadam@uni-siegen.de

Abstract

Institutions matter. The significance of how “formal and informal rules of the game” impact social and political phenomena has long been recognized, and questions surrounding how institutions break down, change, adapt, and are renewed are of particular interest. One important approach within this field is to consider that it is not merely material interests which are important in institutional questions, but that ideas play an important role in affecting institutions as well. Explanations of institutional change in the ideas and institutions literature have focused predominantly on structural factors at the expense of taking agency into account in any serious way. The “new institutionalism” has an “agency problem” wherein how to theorize agency in any substantive manner has been found wanting. I highlight here how Historical Institutionalism, one of the institutionalisms which has most concertedly dealt with ideational matters in the social sciences, has developed over the past three decades, how it still has not succeeded in understanding agency sufficiently well, and what an approach might consist of to address this problem. In particular, I suggest that meso-level theorizing is necessary to move away from micro-level explanations of institutional change. Entrepreneurship provides a promising perspective how to consider agency, and I offer two perspectives through which this might be attained. One consists of examining the interaction effects between different micro-theories of entrepreneurship, another of examining specific forms of entrepreneurship like “judgment-based entrepreneurship.”

Ideas & Institutions

Ever since the late 1980s, the role ideas play in effecting political outcomes has received renewed attention in the social sciences. A turning point for this type of research consisted in deficiencies in explaining social phenomena merely through the concept of “interests” inherent to rational choice. Because it was understood that individuals, groups, and organizations pursuing their self-interest could not explain the coming into being of the social world in full, research increasingly began taking into account the role that “ideas” play and what their impact is in historical, commercial, social and political settings. Ideas can take many different flavors, and one of the most prominent taxonomies of ideas is that they are (1) worldviews, (2) principled beliefs, or (3) beliefs about cause-and-effect relationships.[i] Scholarship in the succeeding decades has operationalized research on ideas in very different directions, and there are now many different approaches to studying the impact ideational matters have on the constitution of social phenomena.

The “new institutionalism” was a particularly promising strand of research which allowed for the infusion of scholarship on ideational matters, leading to a wealth of different approaches and outcomes on ideas and their impact on policy.[ii] Initial research on the role ideas play in institutional change conceived of three different approaches for study: rational choice institutionalism, sociological institutionalism, and historical institutionalism.[iii] Within Rational Choice Institutionalism (RCI), it is assumed that actors have fixed interests and that interests are distinct from agents’ ideas. Ideational explanations are of interest in those cases, in particular, when explanations based on material interests are insufficient. Sociological Institutionalism (SI), contrarily, highlights “the logic of cultural appropriateness.” Ideas in this context consist of norms which govern the action by agents. Cultural norms may thus offer an incentive structure for agents, according to which action can be explained. Historical Institutionalism (HI), in its original version, upheld the idea of historical path-dependence in which institutional stability was presumed; when structures broke down, it was assumed, did it become possible for new path dependencies to be set in motion. During these moments—often referred to as “critical junctures”—actors were able to incorporate ideas they held to bring about institutional change. More recently, HI and its outgrowth, Constructivist Institutionalism (CI), have shifted towards accepting that “ideas” and “interests” are not anti-thetical or mutually exclusive entities but are rather co-constitutive. An ontological question surfaces here in examining what constitutes actors’ interests? For CI and constructivist-leaning HI scholars, interests are themselves cognitively generated and informed by the ideas actors have. In short, it is the interplay of ideas and interests which are examined in contemporary research on ideas and institutions, how they are operationalized, how they can be studied analytically, and how they become efficacious in various settings.

Historical Institutionalism: From Exogeneity to Endogeneity. From Structure to Agency?

As the name itself reveals, HI, from its earliest inception, placed an emphasis on history in explaining institutional durability, development, and change. HI scholars argued that history mattered because 1) political events occur within historical context (i.e. what occurs is strongly impacted by when it occurs), 2) that political decisions which are cast are always dependent on previous choices and simultaneously also affect future choices at subsequent decision points, and 3) that expectations are moulded by the past.[iv] In so doing, early accounts of HI adopted a perspective that was both deeply structuralist and materialist, and there was a predilection to explaining why institutions were stable and durable. Precisely because early versions of HI were regarded as excessively “sticky” and focusing disproportionately on path-dependency and institutional stability, not on path-altering moments and institutional change, criticism was aimed at its overly stationary perspective. The perceived necessity to explain disequilibrium shifted the focus of scholarship to accounts of complex institutional evolution, adaptation, and innovation.[v]

While HI opened up increasingly in the direction of explaining change—not institutional stasis—different approaches emerged in how change was explained. On the one hand, change occurring through exogenous means in moments of contention revealed a perspective that path-dependencies could be broken in particular circumstances, provided that external circumstances allowed for a challenge of the status quo.[vi] The focus here was typically on macro-historical occurrences, such as wars, revolutions, economic crises, and alike—anything precipitating radical uncertainty. The open-endedness of these particular circumstances subsequently enabled transitions leading to new trajectories of institutional stability, setting new path-dependencies in motion.[vii] On the other hand, a different stream of scholarship within HI emphasized that change can indeed arise endogenously from within; here, change need not occur decisively in a grand moment of history, transitioning abruptly from one form of institutional stability to another. Rather, institutional change can be gradual and incremental, transpiring in bits and pieces over time.[viii]

While this latter strand of HI thought has made enormous progress in explaining “more mundane” cases of institutional development and evolution, a further complicating issue still exists, however. For while this development to focus on endogenous change in HI has led to progress in understanding how institutional change may occur, it has only slowly come to establishing the importance of agency in bringing about change. The challenge to consider agency is a serious departure from HI’s traditional tendency to focus on institutional evolution largely predetermined by structural factors. Conran and Thelen note that “the challenge has been to inject agency into institutional accounts, but in a way that generates portable propositioning to identify broader patterns.”[ix] They suggest that the recognition of the omnipresence of agency is the challenge for the study of institutional change, noting that “agency [exists] all the time and not just in the very rare moments when structures break down entirely.” After all, “[i]n political life, unstructured agency is as unthinkable as are structures with no agents.” [x]

Yet herein lies the problem: on the one hand, there is an understanding that agency exists all the time; on the other hand, the concept of agency still faces a certain vacuity. How does one understand agency and what does it imply for theories of institutional change? Little is understood concerning what constitutes agency or how it can be better theorized for research on ideas and institutional change. While there is an acknowledgement increasingly that agency is important, it is also not uncommon for HI scholars to shirk the issue.[xi] Agency is viewed as a “black box”—it is understood as important, but, at least within the ideas and institutions community, it is also largely unspecified.[xii] Nor does this “agency problem” apply solely to HI.[xiii] In spite of CI’s traditional insistence on discontinuity and indeterminacy, it likewise has not solved the conundrum surrounding agency.[xiv] Constructivist-leaning scholars have certainly criticized rational choice institutionalist scholars for their functionalist perspective on the matter, suggesting essentially that they deny genuine agency:

Yet despite its putative concern with individual choice, rational choice strips away all distinctive features of individuality, replacing political subjects with calculating automatons. Rather than accounting for the choices of a situated subject, it describes what any utility maximising chooser would do in a given situation. In this way, rational choice analysis moves from an apparently agent-centred individualism exhibited in choice, to a deep structuralism, deriving action from context.[xv]

In this sense, “actors [are seen] as the prisoners of the institutions they inhabit.”[xvi]

More importantly, however, constructivist criticism also extends to HI scholarship. In this view, more sticky versions of HI do not hold a misguided view of agency like rational choice institutionalists do, but they largely overlook it—or do not appreciate it sufficiently—as a causal factor in explaining institutional change.[xvii] At the same time, more recent, flexible versions of HI made agency epiphenomenal. Scholarship was so consumed with explaining endogenous change that they subordinated everything to it, thereby making a mockery of agency. As Blyth notes: “The pursuit of an all-encompassing theory of endogenous change…has resulted in a strong theory of institutions becoming a derivative theory of agents and coalitions formed under environmental uncertainty and rule ambiguity.”[xviii]

While these criticisms are certainly on the mark, it also reveals that the assumption inherent in constructivist approaches generally consists of recognizing merely that agents’ actions matters for institutional outcomes in political settings, and that these must be taken into account for any theory of institutional change. Yet this is not a particularly sophisticated understanding of agency: to argue that agents’ actions matter—while correct—reveals little about how it matters or how agents’ action can be theorized. Consequently, even within mainstream constructivist thought, there is little agreement as to what constitutes agency.[xix] Moreover, if agency simply happens, it faces the prospect of being regarded as a stable, omnipresent variable impacting social and political phenomena consistently. Always existing, agency could thus be viewed, not as a factor whose indeterminacy causes differentiating political outcomes, but as a unifying variable with its accompanying institutional effects. The danger is, in other words, that agency loses its volitional character and with it its disparity of outcome. Similar to the criticism directed against early ideational scholarship of understanding ideas in a residual sense, agency faces this same danger of becoming residual.[xx] If its existence and transpiring are given, its impact on particular outcomes is inconclusive.

The result of research in HI and CI has, on the whole, consisted of efforts to date which highlight isolated cases demonstrating that individual actors may indeed take on important roles in engaging in strategic action and thereby contribute to institutional change. What these accounts have not achieved so far, however, has been to grasp agency in a more overarching fashion, whereby the concept could thus lose some of its non-specificity and whereby theoretical progress could be achieved in grasping it analytically. What is required, instead, are proper specifications so that one can formulate a better understanding of the agency-related dynamics contributing to institutional change.

Meso-Level Explanations as a Theoretical Desideratum

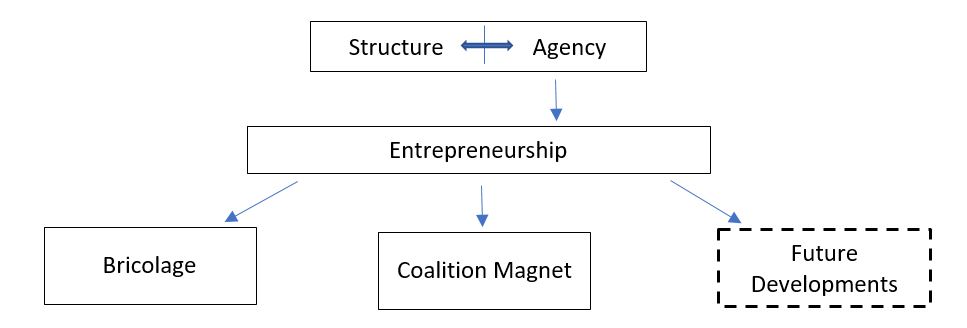

There are ample examples in the literature which highlight that individuals take on decisive roles in seeking to transform political conditions.[xxi] And while first efforts towards specifying agency and the role actors may take on in this process have already been undertaken, these approaches can hardly purport to move the debate on agency forward considerably. The main problem is that these undertakings, while seeking to provide more sophisticated conceptions of agency, incur unnecessary restrictions. Consequently, this restrictiveness makes their application at theoretical level problematic because they unnecessarily rule out cases which could in fact be considered to be agential. Exemplary for these approaches are the concepts of bricolage and coalition magnets.[xxii] As Carstensen notes in formulating his theoretical outlook of the bricoleur, “a micro-theory about how actors actually work with ideas – besides depending on them for mutual cooperation and identifying their interests – is missing.”[xxiii] While this is a welcome call to developing approaches to theorize agency more closely, he goes on to note that “[t]he vision of the bricoleur may thus help spell out the micro-theory that underpins ideational change.”[xxiv] And herein lies the problem: Carstensen’s account is not the micro-theory of agency. It offers one small-scale perspective through which agency can usefully be understood. In fact, both concepts of bricolage as well as coalition magnets are hardly “portable” in understanding agency on a larger scale. Carstensen’s bricoleur approach, for example, rules out any kind of radical institutional change, and the time horizon of bricoleurs is assumed to consist only of action geared towards reaching short-term goals. Béland and Cox, in contrast, suggest that their approach is focused on “wholesale” ideational change, demonstrating how societal attitudes shift in general. But here, too, this theorization presumes that it is a necessary condition to effect wide-ranging changes in beliefs to herald in institutional change. Quite to the contrary, however, institutional change is surely also conceivable for cases in which radical change does occur, where long-term goals are pursued, and where shifts of societal attitudes do not constitute the focus of strategic action by actors. All of these specifications therefore suggest that these micro-theories are too specific; they pay heed to certain types of agency, but preclude other forms of action by agents. What is needed instead is one or multiple forms of meso-level explanations which provide a more encompassing specification of agency.

The figure above highlights this process more closely. I do not intend to relitigate the relationship between structure and agency here, accepting instead that structure and agency are entwined and mutually dependent.[xxv] Yet as opposed to the attempts to date, which skip the middle level and move directly from agency to its very specific micro-theories, much can be learned if we seek to theorize agency (better). As a particularly promising outlook, one may make progress towards developing a more broadly applicable theory to understand how agency is actually utilized to contribute to ideationally-induced institutional change.[xxvi]

Entrepreneurship as Agential Action

Considering that the approaches listed above work with entrepreneurs in political settings—i.e. “political entrepreneurs”—it is not far-fetched to conceive of a meso-theory of agency in terms of entrepreneurship. Especially in light of the recent move of economists to take ideational factors seriously, economists may function as a source of inspiration to initiate theoretical progress for an entrepreneurial approach to ideationally-driven institutional change.[xxvii] This is all the more important, as all of the new institutionalisms—RCI, SI, HI and CI—have either overwhelmingly rejected non-structuralist explanations for institutional change, or they have only tenuously and somewhat superficially employed language from the field of entrepreneurship to provide some explanatory clarity in single, empirical cases.

Yet there are also some problems which arise when conceiving of entrepreneurship at a meso-level. First, what is entrepreneurship? Acknowledging that there is no common definition of entrepreneurship shared by researchers in the field implies that it might be difficult to generate an understanding which can genuinely be considered to be “overarching.” Because there are different domains inherent within entrepreneurship, since the field employs different methodologies, and because the field even works with varying ontological presuppositions, entrepreneurship research is nearly unique in the extent to which it is difficult to rally around common terminology. To be sure, this is what makes entrepreneurship research innovative and exciting, but it also provides a challenge for the task at hand.

This has an impact on a related second point: Because it is difficult to conceive of entrepreneurship in any kind of universal fashion, there have been attempts within the entrepreneurship field to examine subcomponents of entrepreneurship—akin to what I have described as micro-theoretical approaches in the ideas and institutions literature. In one quite instructive example, the concept of bricolage is also employed in the entrepreneurship literature.[xxviii] Yet herein lies a danger for the goal outlined above; namely, that this kind of approach only aims at micro-explanations, i.e. that the meso-level is completely disregarded. In other words, if progress is sought in terms of conceiving agency in terms of entrepreneurship, it will not suffice merely to replicate micro approaches from within entrepreneurship theorizing—a more overarching conception is nevertheless still necessary.

How, then, might it be possible to conceive of entrepreneurship as a solution to theorizing agency at a meso-level in the ideas and institutions literature? Two opportunities stand out. First, one might consider the interaction effects between different kinds of micro-theories. Indeed, since the question under consideration entails moving from micro-approaches to a meso-level, understanding how different micro-perspectives interact with each other could lead to an overarching theoretical approach of entrepreneurship. Second, it might make sense not to theorize some ill-defined concept of entrepreneurship as such, but rather to focus on a specific form of entrepreneurship. “Judgment-based entrepreneurship,” for example, might offer a perspective which hones in on the cognitive elements of agential action, a suitable perspective for efforts seeking to contemplate ideational matters. Either of these approaches could lead to an improved understanding of what constitutes agency and thus shed light on the confusion which exists in discussing ideas and institutions.

References

Abdedal, Rawi, Mark Blyth, and Craig Parsons, eds. 2010. Constructing the International Economy. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Alston, Lee, Marcus Andre Melo, Bernardo Mueller, and Carlos Pereira. 2016. Brazil in Transition: Beliefs, Leadership, and Institutional Change. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Alston, Lee. 2017. “Beyond Institutions: Beliefs and Leadership.” The Journal of Economic History 77 (2): 353-372.

Archer, Margaret Scotford. 2000. Being Human. The Problem of Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Béland, Daniel and Robert Henry Cox. 2016. “Ideas as Coalitional Magnets: coalition building, policy entrepreneurs, and power relations.” European Journal of Public Policy 23 (3): 428-445.

Bell, Stephen. 2011. “Do We Really Need a New ‘Constructivist Institutionalism’ to Explain Institutional Change?” British Journal of Political Science 41 (4): 883-906.

Bell, Stephen. 2012. “Where Are the Institutions? The Limits of Vivien Schmidt’s. Constructivism.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 714-719.

Bell, Stephen. 2017. “Historical Institutionalism and New Dimensions of Agency: Bankers, Institutions and the 2008 Financial Crisis.” Political Studies 65 (3): 724-739.

Berman, Sheri. 1998. The Social Democratic Moment: Ideas and Politics in the Making of Interwar Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bhaskar, Roy. 1997. A Realist Theory of Science. London: Version.

Blyth, Mark. 2002. Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the 20th Century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Blyth, Mark. 2016.“The New Ideas Scholarship in the Mirror of Historical Institutionalism: A Case of Old Whines in New Bottles?” European Journal of Public Policy 23 (3): 464-471.

Blyth, Mark, Oddny Helgadottir, and William Kring. 2016. “Ideas and Historical Institutionalism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, edited by O. Fioretos, T Faletti, and A. Sheingate, 142-162. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, John. 1998. “Institutional Analysis and the role of ideas in political economy.” Theory and Society 27: 377-409.

Capoccia, Giovanni and R. Daniel Kelemen. 2007. “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59 (April 2007): 341-69.

Capoccia, Giovanni. 2016. “Critical Junctures.” In The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia Faletti, and Adam Sheingate, 89-106. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carstensen, Martin. 2011. “Paradigm Man vs. the Bricoleur: Bricolage as an Alternative Vision of Agency in Ideational Change.” European Political Science Review 3 (1): 147-167.

Conran, James and Kathleen Thelen. 2016. “Institutional Change.” In The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, edited by O. Fioretsos, T. Faletti and A Sheingate, 51-70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dabrowska, Ewa and Joachim Zweynert. 2015. “Economic Ideas and Institutional Change: The Case of the Russian Stabilisation Fund.” New Political Economy 20 (4): 518-544.

Desa, Geoffrey and Sandip Basu. 2013. “Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 7 (1): 26-49.

Fearon, James and Alexander Wendt. 2002. “Rationalism v. Constructivism: A Skeptical View.” In Handbook of International Relations, edited by Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse-Kappen and Beth A. Simmons, 52-72. London: Sage.

Fisher, Greg. 2012. “Effectuation, Causation, and Bricolage: A Behavioral Comparison of Emerging Theories in Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (5): 1019-1051.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goldstein, Judith and Robert Keohane. 1993. Ideas & Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions, and Political Change. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Hall, Peter and Rosemary C. R. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936-957.

Hay, Colin and Daniel Wincott. 1998. “Structure, Agency and Historical Institutionalism.” Political Studies 46 (5): 951-957.

Hay, Colin. 2006. “Constructivist Institutionalism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions, edited by Sarah Binder, Rod Rhodes, and Bert Rockman. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hay, Colin. 2011. “Ideas and the Construction of Interests.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by Daniel Béland and Robert Henry Cox, 65-82. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leighton, Wayne and Edward Lopez. 2014. Madmen, Intellectuals, and Academic Scribblers: The Economic Engine of Political Change. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Mahoney, James and Kathleen Thelen. 2010. “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change.” In Explaining Institutional Change, edited by J. Mahoney and K. Thelen, 1-37. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McCloskey, Deirdre. 2016. Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Morrison, James Ashley. 2013. “Before Hegemony: Adam Smith, American Independence, and the Origins of the First Era of Globalization.” International Organization 66 (3): 395-428.

Mukherji, Rahul. 2013. “Ideas, interests, and the tipping point: Economic change in India.” Review of International Political Economy 20 (2): 363-389.

Parsons, Craig. 2016. “Ideas and power: Four intersections and how to show them.” European Journal of Public Policy 23 (3): 446-463.

Peinert, Erik. 2018. “Periodizing, paths and probabilities: why critical junctures and path dependence produce causal confusion.” Review of International Political Economy 25 (1): 122-143.

Phillips, Nelson and Paul Tracey. 2007. “Opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial capabilities and bricolage: connecting institutional theory and entrepreneurship in strategic organization.” Strategic Organization 5 (3): 313-320.

Roberts, Geoffrey. 2006. “History, Theory and the Narrative Turn in IR.” Review of International Studies 32 (4): 703-714.

Rodrik, Dani. 2014. “When Ideas Trump Interests: Preferences, Worldviews, and Policy Innovations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (1): 189-208.

Schmidt, Vivien. 2008. “Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (1): 303-326.

Schmidt, Vivien. 2011.“Reconciling Ideas and Institutions through Discursive Institutionalism.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by Daniel Béland and Robert Henry Cox, 47-64. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schmidt, Vivien. 2012. “A Curious Constructivism: A Response to Professor Bell.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 705-713.

Slater, Dan and Erica Simmons. 2010. “Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents in Comparative Politics.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (7): 886-917.

Soifer, Hillel David. 2012. “The causal logic of critical junctures.” Comparative Political Studies. 45 (12): 1572-1597.

Steinmo, Sven. 2008. “Historical Institutionalism.” In Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences, edited by Donatella Della Porta and Michael Keating, 118-138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steinmo, Sven. 2016. “Historical Institutionalism and Experimental Methods.” In The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia Faletti, and Adam Sheingate, 107-123. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Streeck, Wolfgang and Kathleen Thelen. 2005. “Introduction: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies.” In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, edited by W. Streeck and K. Thelen, 3-39. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widmaier, Wesley, Mark Blyth, and Leonard Seabrooke. 2007. “Exogenous Shocks or Endongenous Constructions? The Meanings of Wars and Crises.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (4): 747-759.

Widmaier, Wesley. 2016.“The power of economic ideas – through, over and in – political time: the construction, conversion and crisis of the neoliberal order in the US and UK.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 338-356.

Wight, Colin. 2006. Agents, Structures and International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zweynert, Joachim. 2018. “Contextualizing Critical Junctures: What post-Soviet Russia Tells Us About Ideas and Institutions.” Theory and Society 47 (3): 409-435.

[i] Goldstein and Keohane 1993, chapter 1.

[ii] For an early overview of research strategies within these sub-fields, see e.g. Goldstein and Keohane 1993; Campbell 1998.

[iii] Hall and Taylor 1996.

[iv] Steinmo 2008.

[v] Hay 2006, 63; Peinert 2018.

[vi] Different terms cover the same general point that exogenous factors are necessary for institutional change: Capoccia and Kelemen 2007 utilize the term “critical junctures”; Alston et al. 2016 refer to “critical transitions”; and Mukherji 2013 and Alston 2017 employ the term “windows of opportunity.” For a criticism on the view that institutional change occurs by moving from one equilibrium to another, see Zweynert 2018.

[vii] For approaches requiring some version of “crisis” or at some point necessitating an exogenous impact, see Capoccia and Kelemen 2007; Slater and Simmons 2010; Soifer 2012; Mukherji 2013; Widmaier 2016.

[viii] See Streeck and Thelen 2005, chapter 1; Mahoney and Thelen 2010, chapter 1; Conran and Thelen 2016.

[ix] Conran and Thelen 2016, 64, emphasis in original.

[x] ibid., 66, emphasis in original.

[xi] This problem also extends to other fields, such as international relations, in that “[r]arely is it clear what agency is, what it means to exercise agency, or who or what might do so” (Wight 2006, 178). Moreover, “even modern constructivists have been largely content to take as ‘exogenously given’ that they were dealing with some kind of actor, be it a state, transnational social movement, international organization or whatever” (Fearon and Wendt 2002, 63, emphasis in original).

[xii] See Capoccia 2016; Steinmo 2016 who employ the language of a “black box”. One recent effort to address the issue of underspecification head-on is Bell 2017.

[xiii] Blyth, Helgadottír, and Kring 2016, 158.

[xiv] Constructivist institutionalism (CI) emerged as a critique to the deficiencies it regarded in HI. On the deficiencies of HI, see Blyth 2002; Hay 2006; Hay 2011. Discursive institutionalism is closely related to CI, and while the two terms are not identical, they share many common features, see Schmidt 2008; Schmidt 2011; Hay 2011. For an intradisciplinary debate on the proper differences and commonalities, see Bell 2011; Schmidt 2012; Bell 2012. On the contentious back and forth between HI and CI, see Dabrowska and Zweynert 2015.

[xv] Hay and Wincott 1998, 952.

[xvi] Steinmo 2008, 174.

[xvii] Hay and Wincott 1998; Widmaier, Blyth, and Seabrooke 2007.

[xviii] Blyth 2016, 466.

[xix] Abdedal, Blyth, and Parsons 2010, 8-14. As a case in point, the index for this volume does not have a listing for the term.

[xx] On the criticism of viewing ideas in a residual sense, see Parsons 2016.

[xxi] Berman (1998) portrays leaders of political parties in interwar Europe as ideational entrepreneurs who are involved in shaping others’ beliefs regarding the constitution of their interests. Morrison (2013) highlights the move towards a liberalized trading structure in 18th century Great Britain, pointing to Adam Smith as an “enterprising intellectual” in his impact on key policymakers in British government. In the case of the founding of the United States, Alston (2017) examines the role of leaders wielding influence through the beliefs they hold, and their methods employed, to bring about a constitution in which states would share power with a central authority.

[xxii] On the former, see Carstensen 2011; on the latter, see Béland and Cox 2016.

[xxiii] Carstensen 2011, 150.

[xxiv] ibid., 160, emphasis added.

[xxv] See Giddens 1984; Bhaskar 1997; Archer 2000; Roberts 2006.

[xxvi] That is not to say that agency must solely be understood in terms of entrepreneurship. Indeed, as Mark Blyth warns, ideational scholarship can learn much from the path HI pursued by placing an elevated focus on institutions that agency became derivative (2016). Pluralism is indeed welcome in this respect, and competing conceptions of agency which offer theorization along different lines will surely only enhance our understanding of ideational change.

[xxvii] Rodrik 2014; Leighton and Lopez 2014; McCloskey 2016; Alston 2017.

[xxviii] Cf. Phillips and Tracey 2007; Fisher 2012; Desa and Basu 2013.