Matthias Sehr, University of Siegen, Research assistant at the chair for Contextual Economics and Economic Education

Contact: Matthias.sehr@uni-siegen.de

Abstract

The discussion about more economic education at schools has received increasing impetus over the past 20 years. Points of controversy are not only the content, but also whether more economic education in schools is needed at all. In times of increasing right-wing populism, the demand for more political education is growing. Whether this approach is sufficient or whether an approach that includes economic education can be helpful has so far been disputed in the academic world. In addition, there are fears on the part of the trade unions that students are being given a one-sided positive image of the market economy and enterprises and that employee positions are being neglected. Despite all the criticism, the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia is venturing more economic education and has introduced the subject „Economics-Politics“ initially at high schools for the 2019/20 school year. Gradually, the introduction is to take place with the coming school years also for secondary schools. A new subject brings with it both a new curriculum and new textbooks. The topic of entrepreneurship takes on a greater role in the curriculum and thus also in the classroom. In the literature, the previous presentation of entrepreneurship in textbooks is criticized for various reasons. Even teachers are not always content with textbooks and search the internet for alternative materials. It is therefore necessary to determine the extent to which current textbooks already cover the many facets of entrepreneurship or where there is still a need for improvement.

What does school tell us about entrepreneurship?

Before you read the whole blog entry, I would like to take you on a short journey. Please take a moment, close your eyes and think about the following question: What do you think of when you hear the word „entrepreneurship“?

Have you thought of a person, maybe in a fancy business suit or maybe a factory building? Was the person male or female, young or old? Was the factory building old and grey with dark smoke from chimneys or a high-rise building with a glass front?

The following pictures give a brief insight into what the first search results on the Internet are.

The image you had before your eyes has been pieced together piece by piece throughout your life. Some of it may have remained fresh in your mind from the newspaper or other media, others may have been there for many years. Speaking of years, let’s move on to the more difficult second question: When did you first think about entrepreneurship? We can assume that you first dealt with this topic consciously and systematically at school. Depending on the federal state in which you attended school, entrepreneurship was treated more or less intensively. The subject in which you dealt with this topic can also range from history and geography to economics or politics. But what is quite likely is the medium you used at the time: the schoolbook. Even though the topic of digitization (Link) is currently on everyone’s lips, the textbook has not gone out of fashion and is still an essential part of planning and conducting lessons. An insight into the significance of textbooks for today’s teaching can be found in Neumann (2015), who interviewed 720 teachers for his study. 50% of the teachers surveyed considered textbooks to be of outstanding importance for their lessons. Another 20% stated that the textbook is at least important for their lessons. Looking at why the textbook is so popular, quite pragmatic reasons are given. More than two thirds of the teachers say that easy access is guaranteed by the textbook lending system. It makes it easier to prepare for lessons and provides a guiding thread for the entire school year. Besides, they are in line with the curriculum and thus offer a secure preparation for final exams (Neumann 2015, p. 90). In a certain way, textbooks reflect „interpretations, thought patterns and values that are politically desired and also tend to be socially negotiated“ (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 6, translation by the author). The approval of textbooks by the state controls the production of knowledge, which can be regarded as the secure level of knowledge in society (ibid.). What makes teachers less motivated to use textbooks in class, on the other hand, is the quality assurance of textbooks through textbook approval. But how does such a textbook approval process work and what could be the reason why teachers do not trust this kind of quality assurance so much?

To be allowed to use textbooks in school lessons, in Germany you usually need the approval of the respective federal state. The responsible Ministry of Education then carries out a so-called approval procedure. This exists in twelve of 16 federal states (Fey, 2015, p. 36). Only Berlin, Hamburg, the Saarland, and Schleswig-Holstein do not require such an examination. Since education is a matter for the individual states, the procedures differ gradually from one another. In principle, however, three types can be distinguished: 1. the review by one or more reviewers, 2. a self-declaration by the publisher that one complies with the regulations of the federal state, 3. blanket admission for works intended for certain types of schools or subjects (music, art or vocational schools). As a rule, the types of examinations are combined. A license based solely on the publishers‘ self-declaration does not exist in any federal state. In the worst case, a positive expert opinion and the self-declaration of the publishing house are sufficient for admission. Further findings by Neumann (2015) show that the quality of textbooks is viewed critically by teachers. Only ten percent of the teachers surveyed can agree with the statement that the textbooks currently offered are of high quality. 70 percent rather or more or less agree with this statement. The author does not specify exactly what is meant by quality. Positive and negative answers can also be found equally in the question of the extent to which textbooks are the best learning tool.

What textbooks have told us so far about entrepreneurship

But what can we say about how and in what quality the topic of entrepreneurship is presented in schoolbooks? In general, when analysing economic content in textbooks, it should be noted that, with few exceptions, no specific subject exists. Exceptions are Thuringia and Bavaria, which can already look back on decades of tradition. Baden-Württemberg introduced the school subject „Economics, Vocational and Academic Orientation“ (translation by the author) in 2017 and, as already mentioned, North Rhine-Westphalia introduced the subject „Economics-Politics“ for the current school year. Since economics is often not taught in a separate school subject, economic content can also be found in the subjects of history and geography. For this reason, research usually also examines textbooks in these two subjects.

Previous studies on entrepreneurship in textbooks

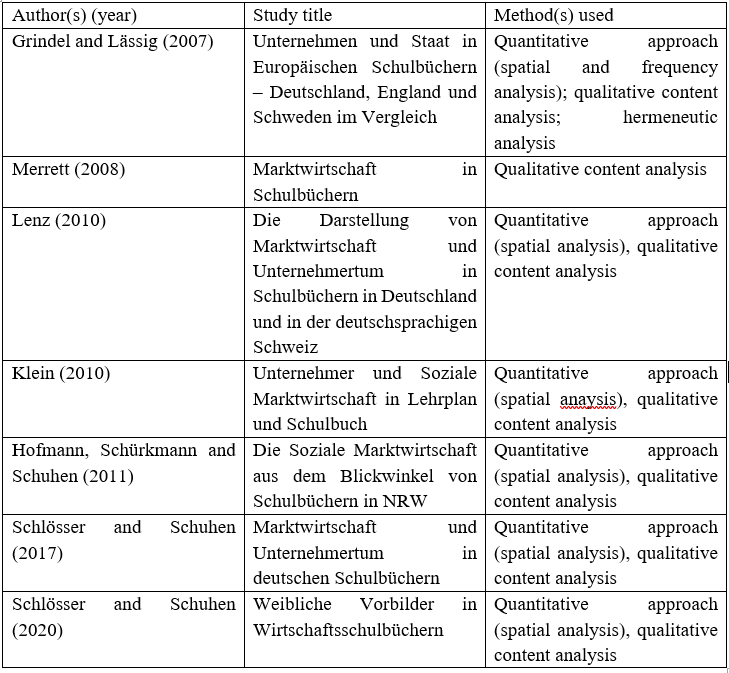

To provide an overview of the current state of research in the field of textbook research on economic topics, the results of selected studies are presented below. The studies differ, however, in some cases significantly in their scientific quality, depth of analysis, and data volume. None of the previous studies provides a complete survey of textbooks, but tendencies become apparent. Merrett’s study shows weaknesses in its research design compared to other studies. The results are rather anecdotal. The studies by Klein (2010) and Hofmann et al. (2011) focus only on the role of entrepreneurship within the social market economy system. In doing so, they ignore the other contexts in which entrepreneurship in textbooks is examined. Therefore, the results are not necessarily representative of the overall representation of entrepreneurship in the textbooks studied. Among the other studies, the one by Grindel and Lässig (2007) offers the unique opportunity to compare textbooks internationally and is not limited to one aspect of entrepreneurship. A similarly broad concept of entrepreneurship can be found in Schlösser and Schuhen (2017). The topic of gender, to which Schlösser and Schuhen (2020) have addressed themselves, is very new and has not yet been examined in this way.

For their analysis, Grindel and Lässig (2007) combine spatial and frequency analyses with methods of qualitative content analysis and hermeneutic techniques (ibid., p. 15). Spatial analysis shows how much space a topic occupies concerning the overall presentation or other topics. Frequency analysis is used in this paper to analyze assignments as well as pictures, tables, and graphics. Qualitative content analysis is used to determine the extent to which topics are presented „comprehensively or incompletely, multi-perspectively or one-sidedly, sophisticatedly or in an easily understandable way“ (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 16, translation by the author). The hermeneutic analysis deals with the underlying understanding of the problem as well as the presentation on a narrative or visual level. The authors themselves see their study as an „exploratory study of images and values transported in textbooks (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 16, translation by the author).

The study „Companies and State in European Schoolbooks – Germany, England, and Sweden in comparison“ (Translation by the author) was published in 2007 by Grindel and Lässig. It has a special characteristic, as it works on an international comparative basis. This type of approach has only been used once more in the last ten years. This study is also very extensive in terms of the number of textbooks examined and the methodological evaluation of these. A total of 142 textbooks from Germany, Sweden, and England were examined. In Germany, 58 textbooks from several German federal states were examined. The books come from all school types except the vocational school and primary school and are suitable for an age range between 10 and 19 years. For the investigation of the English textbook market, 66 textbooks were analysed. These are aimed at pupils at secondary level I and II (11-18 years). Due to the long duration of primary education in Sweden, textbooks from primary school were also examined. In general, the textbooks cover the age range between 11 and 20 years. Since the Swedish textbook market is monopolistic, only a few publishers are offering a small number of books. Therefore only 18 textbooks were analysed. It can be noted that the market for textbooks in Germany, England, and Great Britain differs significantly. The differences between the textbooks in Germany are especially regional, but also very different on a qualitative and conceptual level. This can be attributed to the fact that education is a matter for the federal states. Such differences are not to be found in Sweden and England (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 13 f.).

Aspects of entrepreneurship

Grindel and Lässig (2007) conclude that the entrepreneur often does not occupy an important position in German textbooks. Rather, he is seen as part of the economic system or economic structural change. History textbooks are an exception to this rule, as they shed light on the figure of the entrepreneur, especially in times of significant structural change, such as the Industrial Revolution. In depicting the early phase of industrialisation, outstanding inventors are often portrayed. In the further sequence of industrialization, the focus on the entrepreneur as a person diminishes, and technical developments and structural conditions are thematized instead. Due to the fragmentation of the textbook market by federal states, regional aspects of economic history can be found in a few books. About the depiction of the entrepreneur in the 19th century, Grindel and Lässig (2007) state: „The image of the entrepreneur, which many history books for the 19th century convey, moves between technology pioneer, capitalist, and industrial prince“. (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 25, translation by the author)

Examples of entrepreneurship from North America are used in the chapters on the 20th century. Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller are popular examples. If one looks at the first half of this century, the political events of the Weimar Republic and National Socialism come to the forefront. The cooperation between companies and the Nazi regime is mostly mentioned, but the question of guilt, responsibility, or resistance is avoided (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 25). The presentation of the period from the post-war period to the present largely dispenses with entrepreneurial personalities. Instead, institutionalisation has led to anonymisation, so that individual persons in public limited companies, trade associations or globally active corporations no longer stand out. Grindel and Lässig also note that books for social science or geography lessons use even fewer examples of entrepreneurs. Female entrepreneurs are also very rarely listed as examples.

Corporate forms and structures are again the subject of particularly detailed discussion in history books. Here the functional change from paternalistic management by founders and owners to professional management by experts is traced. The development of personnel structures and forms of enterprise as well as social structures are explained in social history (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 27f.). The textbooks on the subject of social science only deal with current forms of companies. Large industrial companies in particular are used as examples, with small and medium-sized enterprises hardly ever being presented. The teaching of some books relies on practical experience instead of a theoretical basis, which the students are supposed to gain, for example when founding a student company. The textbooks for geography lessons focus primarily on location factors when describing business structures. The majority of the books deal with changes in economic structures and the business landscape.

If one looks specifically at the entrepreneurial image, country-specific differences become apparent. All textbooks deal with the role of the entrepreneur in the early and highly industrialised phase. The presentation is mostly very positive. Entrepreneurs are given attributes such as „farsightedness, inventiveness, creativity, willingness to perform and take risks as well as social responsibility“ (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 92, translation by the author). English history books in particular stand out for their particularly positive presentation. English social science and geography books also take a critical look at entrepreneurship, using examples from the present. A more balanced picture can be drawn for German textbooks. An exuberantly positive presentation is avoided here. Swedish textbooks are characterized by a high degree of practical and life-world orientation, which addresses both the light and dark sides of entrepreneurship (willingness to perform and take risks vs. chances of success and responsibility). The Swedish books on social science stand out in particular because they often use small and medium-sized enterprises as examples and deal with issues relating to setting up a business. This approach is rarely found in German and English books.

The spatial analysis shows that in German and Swedish textbooks about 20% of the contents deal with economic issues. In English textbooks, the proportion is slightly lower at 15%. For all the countries studied, different priorities and perspectives are used depending on the subject area. For example, a historical account is predominant in the history books. Structural changes in the economy and society are classified with global references. The Industrial Revolution is used as an example in all countries. Especially in England, it plays a central role due to the country’s history. For the books in social science, it must be noted that they only refer to the present and current developments and lack a historical perspective. As in the history books, global processes are also dealt with here. In particular, these textbooks focus on the pupils‘ relationship to the world in which they live. From the field of entrepreneurship, the aspect of self-employment, which can be found in almost all books, should be mentioned here (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 91).

The results of Grindel and Lässig (2007) can also be found for Schlösser and Schuhen (2017). Again, depending on the textbook, there are variations in the quality of the presentation of different aspects of entrepreneurship. However, they concentrated only on current textbooks in Germany and looked in more detail at the different subjects and school types than Grindel and Lässig (2007) did. In their study, the authors also compare their results with the study by Lenz (2010), which uses a similar research design. This makes it possible to see to what extent points of criticism from the previous study were taken up by publishers. Although the production of a textbook usually takes several years, a development could well have taken place, as there are seven years between the two studies

Since economic content is not taught in a central subject, textbooks from the subjects of geography, history, social sciences, politics/economics, labour/economy/technology, and economics were examined. In the context of entrepreneurship, the extent to which entrepreneurial dynamics and structural change are addressed was examined. „Creative destruction“, as Schumpeter describes it, includes both innovation and the disruptive moment of structural change. Which of the issues is addressed in the textbooks was a subject of analysis. In addition, the presentation of entrepreneurial personalities was investigated. Are the life paths positively described, possibly as signs of self-realization or the claim to create wealth? Or are greed and ruthlessness put in the foreground? Another question is to what extent self-employment is shown as a desirable or risky option for the pupils‘ career paths. The next sections will provide an overview of the results.

For the subject of geography, it is shown that the entrepreneurial image is presented in a rather one-sided way. The entrepreneur is mentioned positively as an inventor, but not as an innovator. However, entrepreneurship is not discussed in terms of small and medium-sized enterprises, taking large companies such as Nestle or Toyota as examples. The presentation in the subject history is similar. Particularly at the lower secondary level (up to class 10), entrepreneurial personalities are always mentioned as inventors and not as innovators, and are treated only very briefly. From secondary level II onwards, the presentation becomes more detailed but remains to explain the technical innovations and not the persons associated with them. The assessment of structural change at the time of industrialisation is largely negatively evaluated in the textbooks of lower secondary level. Here, too, the presentation changes at the upper secondary level and is more differentiated. In the textbooks on the subject of social sciences, only one book gives an example of entrepreneurial personalities. The role and function of enterprises are dealt with in varying degrees depending on the textbook. Often a kind of „name-dropping“ can be observed. Particularly large or well-known companies are listed, but what they produce, why they became so large, or why they operate globally is not discussed. Aspects of entrepreneurial dynamics such as the making of decisions and their effects are completely absent from textbooks in the social sciences. Even the foundation of an own company is only taken up by two textbooks (Schlösser and Schuhen, 2017, p. 27).

A mixed picture can be drawn for the subject labour/economy/technology. Although there are books that deal with the subject of enterprises in a student-oriented way, they completely disregard the entrepreneurial personality. The structural change is presented especially as a change in the world of work, but otherwise, it is viewed very sceptically. Technical progress is portrayed negatively, as it costs jobs. Possible solutions are seen in the payment of subsidies by the state. The presentation of the aspect of self-employment, which is dealt with in detail in various textbooks, is to be emphasised positively. Here the school subject work/economy/technology differs significantly from the other school subjects.

Most recently, textbooks of the subject economics were examined. The textbooks are generally attested a high professional level and a scientific orientation. However, entrepreneurship is also only presented here in a shortened form. Entrepreneurial personalities are not discussed here either. The importance of entrepreneurship for prosperity and innovation is not included in the textbooks. As in the subject Work/Economy/Technology, the area of self-employment and business start-ups is also dealt with in detail here. The characteristics of a founder play a central role here.

At the end of their study, the authors Schlösser and Schuhen (2017) compare their results with the similarly structured study by Lenz (2010). In doing so, they find that little has changed in the books on geography. However, they emphasise that a more balanced presentation is now more frequent and aspects are less often viewed from one point of view. No improvement in the presentation of entrepreneurship can be observed. A similar finding is also available for history. Here, there is particular criticism that entrepreneurs continue to be presented only as inventors, but not also as innovators. Furthermore, only large companies continue to be used as examples and the existence of small and medium-sized enterprises is not addressed. According to Schlösser and Schuhen, there has been no improvement whatsoever in schoolbooks in the subject of social sciences. The points of criticism mentioned above were already to be found in 2010. The books are recommended for the subject of economics, which does not cover all areas of entrepreneurship equally well but differs significantly from textbooks for other types of schools.

Approaches to teach entrepreneurship

The results of the qualitative content analysis show that the subject of economics is given high priority in the textbooks of all three countries. However, fundamentally different approaches of the countries become apparent. In German textbooks, for example, great importance is attached to basic knowledge such as the definition of technical terms. Grindel and Lässig (2007, p. 91, translation by the author) state: „Three quarters of the textbooks provide differentiated information about the basic concepts of the economic system, almost half about entrepreneurs and companies, three quarters again about interest representation and even more than three quarters about the state, its organisation and its tasks. A completely contradictory way of communicating is evident in the English language works. In these books, case studies are used, so that basic information on the economic system, entrepreneurship, interest groups and the state can only be found in 10 to 16% of all books. Swedish textbooks lie between these two extreme positions.

English and Swedish textbooks are each aimed at a specific grade level and begin with a clear and practical teaching approach, while demanding and theoretical content is only dealt with in higher grades. The German books distinguish not only by grade level but also by school type. It can be seen that the textbooks for different secondary school types are all highly practice-oriented and prepare students for the world of work. However, this world of work is mainly the world of employees and less the world of self-employed or entrepreneurs. The textbooks for higher grades tend to work in a more science-preparatory way and are not significantly different in their depiction of the world of work than the books for the other school types (Grindel and Lässig, 2007, p. 91).

Entrepreneurship and Gender

Schlösser and Schuhen (2020) have taken up a quite new research aspect in their investigation. They examined 20 textbooks about the spread of female role models such as female entrepreneurs and managers. This study is so far the only one that deals with gender aspects in economics textbooks. The selected textbooks are used in different federal states and different types of schools. The textbook analysis shows that even in current textbooks, the problems identified so far still exist. For example, even at present small and medium-sized enterprises are hardly ever discussed as an example of enterprises and certainly not in connection with women in leading positions. The economic and social functions of entrepreneurship are still inadequately described in textbooks. Traditional role models are in most cases reproduced without a critical look (Schlösser and Schuhen, 2020, p. 15f.). Women tend to be portrayed from the perspective of the female employee. The founding of companies, on the other hand, is shown as a matter for men. The authors can cite only a few positive examples. On average, 13 out of every 100 pages of a book contain a directly or indirectly gender-sensitive reference (Schlösser and Schuhen, 2020, p. 11).

Conclusion

It can be stated that the aspects of entrepreneurship dealt with depend on various factors. First of all, there is the school subject in which the economic issues are covered. For example, in the subject history, the economic development of the last three centuries is especially traced. The Industrial Revolution is a central example. Such a perspective is largely dispensed within other subjects. The type of school also plays a decisive role which contents are taught. For example, textbooks at secondary schools are much more strongly oriented towards the students‘ later work environment than in high schools. Entrepreneurship is taught most extensively at vocational schools. Here the focus is on the foundation of a company, which otherwise plays only a minor role in almost all other school types. In the examples used, it can be shown across all studies that small and medium-sized enterprises have hardly any place in the textbooks. By contrast, global corporations such as Toyota are frequently used examples. Moreover, even in current textbooks, supposedly outdated role models continue to be used. Since the criticisms raised have been criticised in various studies for many years, it is questionable whether the new textbooks for the subject of Economics-Politics can show progress in this respect.

References

Fey, C.-C. (2015): Kostenfreie Online-Lehrmittel: Eine kritische Qualitätsanalyse, Bad Heilbrunn.

Grindel, S., Lässig, S. (2007): Unternehmer und Staat in europäischen Schulbüchern. Deutschland, England und Schweden im Vergleich, Braunschweig,

Hofmann, M., Schürkmann, S. and Schuhen, M. (2011): Die Soziale Marktwirtschaft aus dem Blickwinkel von Schulbüchern in NRW. Siegener Beiträge zur Ökonomischen Bildung, (3).

Klein, H. E. (2010): IW‐Schulbuchanalyse. Unternehmer und Soziale Marktwirtschaft im Schulbuch in Nordrhein‐Westfalen. Eine Untersuchung der Schulbücher für die Unterrichtsfächer Arbeitslehre, Erdkunde, Geschichte, Gesellschaftslehre, Politik, Sozialwissenschaften und Technik, Köln.

Lenz, J. (2010): Die Darstellung von Marktwirtschaft und Unternehmertum in Schulbüchern in Deutschland und in der deutschsprachigen Schweiz, Potsdam.

Merret, G. (2008): Marktwirtschaft in Schulbüchern, Potsdam.

Neumann, D. (2015): Bildungsmedien Online. Kostenloses Lehrmaterial aus dem Internet: Marktsichtung und empirische Nutzungsanalyse, Bad Heilbrunn.

Schlösser, H.-J., Schuhen, M. (2017): Marktwirtschaft und Unternehmertum in deutschen Schulbüchern, Berlin.

Schlösser, H.-J., Schuhen, M. (2020): Weibliche Vorbilder in Wirtschaftsschulbüchern, Potsdam-Babelsberg.