Anna-Katharina Schaper, doctoral candidate, Chair of China Business and Economics, University of Würzburg and external doctoral student at the Professorship of Business Administration, in particular of SME Management and Entrepreneurship, University of Siegen.

Contact: anna-katharina.schaper@uni-wuerzburg.de

Abstract

Entrepreneurship in China, particularly from a gender perspective, is an underexplored research field. Does scarcity of research on China imply that China is not a relevant case for entrepreneurship scholars and practitioners? Does private entrepreneurship in China matter after all? Should we stay on the course of investigating entrepreneurship activities in conventional environments, like the US and its Silicon Valley? Or is it about time to calibrate our research focus and turn to studying entrepreneurial activities in less explored contexts? To answer these questions, this article provides a quick overview of the history of the Chinese private sector and offers an analysis of the status quo of the Chinese entrepreneurship landscape. Additionally, the article uses a gender-lens to shed light on entrepreneurial endeavors of Chinese women entrepreneurs.

Traveling into the past: a quick overview of the historical development of private entrepreneurship in China

When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949, the government gradually suppressed and forbid private entrepreneurship (Ahlstrom and Ding, 2014). Guided by a system of ‘state capitalism’, the government transformed private firms into state-private cooperatives in the early 1950s, merged individual handicraft businesses to larger cooperatives as well as transformed them into local, state or commune factories. However, after the Great Leap Forward (1958–1959), the Chinese government eased their restrictions regarding individual small and individual handicraft businesses and allowed them to operate again. Nevertheless, a few years later, small businesses were again forbidden during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) (Garnaut et al., 2012). Within two decades, the political environment transformed China’s economic system, with the economy system now relying on its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and collectively owned enterprises at the local level.

In December 1978, the initiated opening-up reforms laid the foundation for a step-by-step re-introduction of the private sector as well as for a once again changing economic path (Nie et al., 2009). In the beginning of the reform period, private entrepreneurship was limited to sole proprietorships, so-called ‘getihu’ (个体户), which were only allowed to employ a maximum of seven people. It took until June 1988 to formally introduce the private sector by issuing the ‘Tentative Stipulations on Private Enterprises (TSPE)’. The TSPE enabled enterprises to hire more than seven people and therefore to officially operate and grow private businesses, the so-called ‘siying qiye’ (私营企业) (Garnaut et al., 2012).

With the slogan of “grasp the large, let go of the small (抓大放小)”, the Chinese government acted upon inefficiencies in its state sector and initiated a wave of SOE reforms and privatization measures in the 1990s (Lardy, 2014). Meanwhile, China’s economy grew at a rapid pace, with double-digit growth rates being the norm until the early 2000s (see World Bank 2022 database). Regarding economic growth, the private sector became a more and more important driver of economic growth. Nevertheless, China’s economy grew on a slower pace starting from the 2010s. XI Jinping (President of the People’s Republic of China and General Secretary of the CCP) referred to this as the ‘New Normal’, an economic system relying on a more sustainable growth model (Dittmer, 2017). In this regard, the government aimed to change its growth model from being the ‘workbench of the world’ (low-tech and labor-intensive manufacturing sector) to being an innovation and manufacturing powerhouse. This is mirrored also in the introduction of the Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Strategy (2014) and the ‘Made in China 2025 strategy’ (2015).

The journey of China’s private sector is for several reasons, quite remarkable. First, private-owned enterprises clearly outnumber state-owned enterprises nowadays. In 2020, 25.055,456 companies were registered in China, with 91.11 percent (22.835,565) of these being private-owned enterprises. In contrast, only 0.03 percent (82,155) of China’s enterprises being SOEs. All other enterprise types (such as foreign enterprises and collective enterprises) accounted for 2.219,891 enterprises and made up for 8.86 percent (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021). Second, the private sector has become the driving force and backbone of the Chinese economic system. It nowadays contributes to more than 50 percent of tax revenue, 60 percent of the economy’s GDP, 70 percent of technological innovation, 80 percent of urban employment and 90 percent of new created employment (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). Scholars and newspapers even referred to this as the 50/60/70/80/90 rule of private entrepreneurship in China (e.g., Zitelmann, 2019).

However, the relatively few Chinese SOEs contribute to roughly 30 percent of the nation’s GDP (Zhang, 2019) and are giants in the world of business. Examples can be found in the Fortune Global 500 Ranking. The Fortune Global 500 are the biggest companies in the world in terms of revenue. In August 2020, Fortune titled the following headline “The Fortune Global 500 is now more Chinese than American“ (Murray and Meyer, 2020). For the first time in its history, the number of Chinese companies included in the Fortune Global 500 surpassed the number of US-American companies. The 2022 Fortune Global 500 ranking includes 136 Chinese companies versus 124 US-American companies, with Walmart and Amazon from the US leading the ranking and three Chinese companies following in the Top 5 of the world’s biggest companies: State Grid, China National Petroleum, and the Sinopec Group (Fortune, 2022). All Chinese companies included in the Top 5 of the world’s biggest companies are state-owned. In this regard, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) analyzed the ownership structure of the 136 Chinese companies included in the ranking and found 29 POEs versus 71 SOEs (Mei, 2022). This means that in terms of revenue, China’s biggest companies are SOEs. However, private companies such as JD.com (#46), Tencent (#121), and BYD (#436) are included in the ranking of the biggest companies in the world (Fortune, 2022).

In the last years, China’s entrepreneurs needed to navigate turbulent times. First, increased government intervention caused insecurity among entrepreneurs. One example to be named is China’s tech crackdown, which started in 2020 and is still ongoing. For instance, regulators limited the time children are allowed on playing computer games and banned private tutoring services (Reuters, 2021a). The regulations impacted China’s education (tech) industry as well as its gaming industry tremendously. On top of that, COVID-19 and China’s zero-COVID strategy, slowed the economic down. Current predictions show a GDP growth rate of 4.4 percent in 2022 and an expected rebound of the economy of 4.9 percent in 2023 (OECD, 2022). This is well below the GDP growth rates of previous years in China.

Dreaming of unicorns: creating entrepreneurship hubs

Becoming a powerhouse for innovation and entrepreneurship was on top of the government’s agenda in the past years. The ‘Made in China 2025’ and ‘Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation’ strategy are key puzzle pieces in achieving this goal.

The Made in China 2025 (MIC) was announced by China’s State Council in May 2015. MIC is a three-step plan, with targets set to be achieved in 2025, 2045 and 2049. Contrary to what the name, the strategy does not conclude in 2025, it key goals are planned to be achieved in 2049. The year 2049 marks an important milestone for the CCP, since it is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC. As a result, China aims to be a ‘leading manufacturing superpower’ until this historic event. This means that in 2049, the PRC leads global manufacturing and innovation and is competitive in advanced technologies (Zenglein and Holzmann, 2019). To achieve this, the strategy promotes innovation-driven economic growth, particularly by supporting ten core industries: 1) ‘Next-generation IT’, 2) ‘High-end computerized machines and robots’, 3) ‘Aviation and space equipment, 4) ‘Maritime engineering equipment and high-tech ships’, 5) Advanced transportation equipment’, 6) Energy-saving and new energy vehicles, 7) ‘Energy equipment’, 8) ‘Agricultural equipment’, 9) ‘New materials’, 10) ‘Biomedicine and high-performance medical equipment’ (Zenglein and Holzmann, 2019, p. 20). As part of this support, MIC 2025 offers massive funding opportunities for POEs and SOEs.

China’s Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Strategy (大众创业万众创新政策) was announced by the former Premier of the State Council, LI Keqiang at the Summer Davos Forum in Tianjin in 2014. The Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Strategy can be characterized by three key goals: 1) Create employment, 2) Create an entrepreneurial spirit, 3) Foster economic growth and innovation (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2015). Since 2015, the Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week takes place every year in a Chinese city. The first Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week (全国大众创业万众创新活动周)was organized in Beijing (2015), followed by Beijing and Shenzhen (2016), Shenzhen (2017), Chengdu (2018), Shanghai (2019), Beijing (2021), Zhengzhou (2021) and Hefei (2022) (Ecns.cn, 2016; National Eastern Tech-Transfer Center, 2019; State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2022; Xinhua, 2018 and 2020). This entrepreneurship week city list shows that the entrepreneurship week was first held in China’s first-tier cities and subsequently also moved to China’s emerging mega cities in Southwestern and East central China. This shows that the promotion of entrepreneurship and innovation is not exclusively targeting first-tier cities. The idea of mass entrepreneurship and innovation is set to spread across the whole nation.

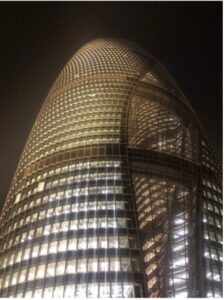

In a study, Gao and Mu (2021) reflect on the successes of the strategy and emphasize that since its announcement, more private business and unicorn start-ups emerged than before. A unicorn company can be defined as “a private company with a valuation over USD one billion” (CB Insights, 2022, n. p.). Unicorn companies have not filed for an IPO yet and are therefore not registered at a stock market. Due to their degree of innovation and potential to contribute to economic growth and job creation, governments seek to nurture unicorns as part of their entrepreneurship ecosystem. Such efforts of China’s dream of creating unicorn hubs could be seen at the 2018 National Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week in Chengdu, Sichuan province (see Photo 1 and 2). Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan province and is a mega city in Southwestern China. Chengdu is particularly renowned for two things: Spicy food and pandas. On Photo 3, you can see Chengdu’s most loved mascot, pandas, jointly exercising with a unicorn. How does this fit into China’s entrepreneurship strategy? We can interpret this arrangement as unicorns being part of Chengdu’s and China’s entrepreneurship environment. Thus, the unicorn is as an illustration of China’s eagerness to create innovative start-ups that eventually become innovative unicorns. Therefore, the government seeks to creating an environment where you can spot unicorns in real-life and not as mythical creatures as they are.

Photo 1–2. Location of the 2018 National Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week in Chengdu, Sichuan province, China

Photo credit: Anna-Katharina Schaper (March 2019).

Photo 3. Pandas and a Unicorn at the 2018 National Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China

Photo credit: Anna-Katharina Schaper (March 2019)

The world is currently home to 1,197 unicorns (see CB Insights unicorn data, 10/21/2022). So, how is China’s unicorn mission going? More than half of all unicorns are located in the United States (n = 646), with China coming second in the unicorn ranking with one out of eight of all unicorns (n = 172), followed by India (n = 70), the United Kingdom (n = 47), Germany (n = 29), and Israel (n = 22). In total, all European Union member countries are home to 100 unicorns. In China, unicorns can be found in 19 cities, with 82.5 percent of all unicorns located in Beijing (n = 62), Shanghai (n = 44), Shenzhen (n = 20), and Hangzhou (n =16) (CB Insights unicorn data, 10/21/2022).

These start-up ecosystems of Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hangzhou are not only the home of most Chinese unicorns, but also belong in terms of performance, funding, market research, connectedness, experience and talent, and knowledge to the best global start-up ecosystems (Beijing #5, Shanghai #8, Shenzhen #23, Hangzhou #36). In 2021, only the Silicon Valley, New York City, London and Boston scored better in these indicators than Beijing (Startup Genome, 2022). Beijing is China’s uncontested unicorn capital. Beijing is famous for tech, while Shenzhen is famous for being the China’s Silicon Valley of hardware. Factors contributing to Beijing’s unicorn success are multifold. Beijing’s tech companies (JD.com, VIPKID, ByteDance, Meituan Dianping) are located in the Zhongguancun (中关村)area (see Photo 4–6). Due to its proximity to Peking University and Tsinghua University, the tech companies have an easy access to the country’s top talents. In the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2022, Peking University and Tsinghua University were ranked as the best Chinese universities, but they also belong to the world’s top 20 universities and share rank #16 (Times Higher Education, 2022).

Photo 4–6. Zhongguancun area and Zhongguancun Entrepreneurship Street in Beijing

Photo credit: Anna-Katharina Schaper (September 2019)

The country’s top universities are not only part of the ecosystem in terms of highly skilled talents, but they also offer acceleration, incubation and entrepreneurship education programs. Examples are Tsinghua’s X-Lab and the Tsinghua SEM X-elerator (Tsinghua SEM-elerator, 2022; Tsinghua X-Lab, 2022). Additionally, Beijing’s vibrant ecosystem can be characterized by its strong gras-roots entrepreneurship communities. For instance, Start-up Grind Beijing, She Loves Tech and Ladies Who Tech, offers lots of networking and entrepreneurship education opportunities in the country’s unicorn capital. Lastly, Beijing offers an extensive number of venture capital funds and business angels. Between 2017-2021, Beijing’s VC funds invested approximately USD 86 bn, which is well above the global city average of USD 4.5 bn (Start-up Genome, 2021).

China’s currently most valuable unicorn start-ups are ByteDance (140 bn USD), SHEIN (100 bn USD) and Xiaohongshu (20 bn USD) (see Table 1). The three companies are based in China’s unicorn hubs and run businesses in different industries. Founded by Zhang Yiming in 2012, ByteDance is the most valuable unicorn start-up in the world. Headquartered in China’s capital, ByteDance operates in the AI industry. Maybe you have not heard about ByteDance yet but use one of ByteDance’s apps. If the TikTok app is on your phone, you are using the company’s product without knowing it. SHEIN comes in on rank #2. The company engages in the field of e-commerce. Its business model has been widely criticized, for copycat clothing, unsustainable, cheap clothing, and its harsh labor conditions (Marwan, 2022). Xiaohongshu is an e-commerce company from Shanghai (Crunchbase, 2022). Xiaohongshu’s co-founder is QU Miranda, a woman entrepreneur who achieved the self-made billionaire status in 2021 (Zamora, 2022). A more detailed analysis of Chinese unicorn companies can be found in a study by me and Prof. Doris Fischer (see Schaper and Fischer, 2021).

Table 1. China’s most valuable unicorn start-ups

| Rank | Unicorn start-ups | Valuation (USD bn) | Industry | City |

| #1 | ByteDance | 140 | Artificial intelligence | Beijing |

| #2 | SHEIN | 100 | E-commerce | Shenzhen |

| #3 | Xiaohongshu | 20 | E-commerce | Shanghai |

| #4 | Yuanfudao | 15.50 | Edtech | Beijing |

| #5 | DJI Innovations | 15 | Hardware | Shenzhen |

| #6 | Yuanqi Senlin | 15 | Consumer and retail | Beijing |

| #7 | Bitmain Technologies | 12 | Hardware | Beijing |

| #8 | Xingsheng Selected | 12 | E-commerce | Changsha |

| #9 | ZongMu Technology | 11.40 | Auto and transportation | Shanghai |

| #10 | Weilong | 10.88 | Consumer and retail | Luohe |

Source: Own illustration based on data from CB Insights (October 21, 2022)

Chinese female entrepreneurs: the story of zhang xin and mi cindy

Have you ever heard about ZHANG Xin (SOHO China), ZHOU Qunfei (Lens Technology), MI Cindy (VIP KID), and WU Yajun (Longfor Properties)? These entrepreneurs belong to the most successful entrepreneurs in the world, some of them even became self-made female billionaires. If you have not heard about their stories and successes, you are not alone. To illustrate the existing gender gap in entrepreneurship and conventional knowledge on Chinese female entrepreneurs, I would like to tell you about an exercise that I do with students in my classes. At the beginning of my classes on entrepreneurship, I ask students to brainstorm names of Chinese entrepreneurs they know. The names usually mentioned are MA Yun (Alibaba), MA Huateng (Tencent), LEI Jun (Baidu), LIU Qiangdong (JD.com), ZHANG Yiming (ByteDance), and LI Bin (Nio). After the brainstorming, we talk about the founders and the business models of the companies they run. After this, I draw the attention of the students to the gender of the respective founders. Once they realize that they predominantly have named male founders, many students feel puzzled and are eager to learn more about gender diversity in entrepreneurship. What does this activity tell us? Does a lack of awareness of Chinese female entrepreneurs imply that there are no female founders that we should know about?

In 2021, nearly 50 percent of the world’s self-made female billionaires were coming from China (Zamora, 2022). This means that according to the Forbes 2022 data, 101 women managed to create extremely successful businesses in the past years. The gender gap in entrepreneurship and a lack of awareness of female entrepreneurs cannot only be observed in China, but in countries all over the world. Additionally, data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor show that in comparison to other countries, China has a comparatively high rate of female founders. For instance, the business ownership rate of females is 8.2 percent in China, and thus above the world’s average. In this category, China ranks 18 out of 50 countries (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2020).

To increase our knowledge on Chinese women entrepreneurs, you will learn in the following about the stories of two Chinese female founders. Both founded their business in Beijing, but in different periods of time. The first one is ZHANG Xin, the founder of SOHO China, who set up her business in the 1990s and belongs to the first generation of female founders in China. The other one is MI Cindy, she set up her business in the early 2010s and represents the new generation of China’s female founders.

If you are in Beijing and visit Sanlitun or other areas in the city, you will see many buildings of SOHO China. SOHO China is a real estate development and property investment company. The company was founded by ZHANG Xin (张欣) and her husband and co-founder, PAN Shiyi in Beijing in 1995 (see Photo 7). Due to the vast number of real estate development projects, ZHANG Xin is renown as ‘the woman who built Beijing’. ZHANG Xin grew up in Beijing during the cultural revolution, at a time when creating such a big private business (that also went for IPO at the Hong Kong stock in 2007), was beyond what anyone could imagine. After China’s opening-up, ZHANG Xin moved to Hong Kong and worked as a factory girl. Her work made it possible to buy a one-way ticket to England. Scholarships enabled her to pursue higher education at the University of Sussex (Economics) and Cambridge University (Development Economics). After graduating from Cambridge University, she worked at Goldman Sachs in London, before moving back to Beijing and to set up her real estate business with her husband in 1995 (Handley, 2017). The rest is history. Nowadays, she is one of the most successful self-made female billionaires in the world. Her story is typical for the first generation of founders that seized opportunities after China’s opening. During that time, double-digit growth rates could be taken for granted. In November 2019, one of SOHO China’s latest real estate development projects was officially opened: The SOHO Leeza tower (see Phot 8 and 9). It is located in Beijing’s Fengtai district and contributes to the development of this new business district in Beijing. The SOHO Leeza tower was designed by Zaha Hadid and is one of her last architecture projects. It is a unique building, with the world’s highest atrium (194.15 m) (see Photo 9) being at its center (Zaha Hadid Architects, 2022). The SOHO Leeza tower can be viewed as an image for the continuing success of ZHANG Xin’s real estate empire.

Photo 7–9. Leeza SOHO opening ceremony on November 19, 2019. ZHANG Xin (see in the center of the photo) and her husband and co-founder PAN Shiyi (second from left).

Photo credit: Anna-Katharina Schaper (November 2019)

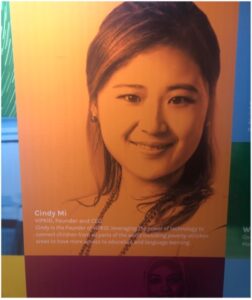

After learning about ZHANG Xin, we will turn to MI Wenjuan (米雯娟), called MI Cindy. MI Cindy is the founder of VIP KID and belongs to the new generation of founders in China (see Photo 10 and 11). VIPKID is an education tech company founded in Beijing in 2013. The company started out to match native English teachers with young students in China. The virtual learning approach therefore provides individual and tailored learning solutions for students (VIPKID, 2022). MI won the EdTech Breakthrough Awards in 2020 and her company was named one of the country’s most innovative companies in 2020 (Fast Company, 2020). However, MI’s own individual education journey was not as smooth as you would think. She dropped out of high school in the 11th grade. Before setting up VIPKID in 2013, she co-founded an education company with her uncle (McCorvey, 2018).

Photo 10–11. MI Cindy at the SheLovesTech Conference 2019 in Beijing.

Photo credit: Anna-Katharina Schaper (September 2019)

Chinese parents want their children to graduate from the nation’s best universities. The entrance to China’s top nine universities (the C9 league), like Peking University or Tsinghua University can be compared to an admission to Ivy league universities. China’s national university entrance exam, the so-called ‘gaokao’ can be literally translated to ‘high exam’. The score in this exam decides which universities students can enter, either a top-tier university, which promises after graduation a rather stable and bright future, or the admission to a lower-tier university, which implies less opportunity and hardness in the already tense labor market. However, the access to the top-tier universities is influenced by regional inequalities (Hamnett et al., 2019). Since the ‘gaokao’ is a defining stepstone in the lives of Chinese students, Chinese parents are willing to spend a lot of money to get their children prepared. With VIPKID, MI Cindy identified the enormous potential of the Chinese edtech market.

The edtech sector benefited from the COVID-19 crisis since it offered digital education solutions. The revenue of the Chinese education tech market increased tremendously in comparison to pre-pandemic levels. From 2018 to 2020, the worth of China’s edtech market grew from 22 to 48 bn USD (Shleifer and Kologrivaya, 2021). Additionally, the edtech industry raised ca. 7.5 bn USD in 2020 (Lee and Sheng, 2021). However, in 2021, XI Jinping categorized after-school tutoring services as a social problem (South China Morning Post, 2021). Linked to the importance of the ‘gaokao’, after-school tutoring services cause an unequal playing field for students from low-income families and make it more difficult for them to compete with students from high-income families for the admission to the country’s best universities. Consequently, the Chinese government regulated the education tech market. Running a business in the edtech industry became more and more difficult since then. Because of the so-called edtech crackdown, the industry needed to react to the newly introduced policies and to adapt their business models. This also applies to VIPKID which now focuses on international markets and no longer provides its services in the domestic market (Reuters, 2021b). Nevertheless, China’s edtech companies are successful. You can find them among China’s Top 35 unicorns in terms of value: Yuanfudao (15.5 bn USD), VIP KID (4.5 bn USD), and Zuoyebang (3 bn USD) (CB Insights, 10/21/2022).

Conclusion and traveling into the future

Since Chinese founders have created a plethora of successful businesses in the past decades, it is surprising that entrepreneurship in China is still an underexplored research field. So, why do we know so little about entrepreneurship activities and how it works in China? More research helps us understand how entrepreneurship works in different regional contexts around the world, particularly from a gender-aware perspective. This article provides an overview of entrepreneurship activities in China and demonstrates why studying entrepreneurship in the land of the pandas is worth the effort. However, ongoing COVID measures, lockdowns, and a zero-COVID strategy make it difficult for businesses to keep up with their performance. This also applies to the research community. Travel restrictions to China are still in place, which renders (field) research very difficult. Nevertheless, we need more researchers paying attention to what is going on in China and to contextualize entrepreneurship activities. Recent political developments and state intervention in the private sector make studying entrepreneurship in China even more timely and relevant.

References

- Ahlstrom, D. and Ding, Z. (2014), “Entrepreneurship in China: an overview”, International Small Business Journal, Vol. 32 No. 6, pp. 610–

- CB Insights (2022), “The Complete List of Unicorn Companies”, available at: https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorncompanies (accessed October 25 2022).

- Crunchbase (2022), “Xiaohongshu”, available at: https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/xiaohongshu(accessed October 25 2022).

- Dittmer, L. (2017), “Xi Jinping’s ‘New Normal’: Quo Vaidis?”, Journal of Chinese Political Science/Association of Chinese Political Studies, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 429–

- cn (2016), “Creative Products Unveiled at China’s Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week”, available at: http://www.ecns.cn/hd/2016-10-13/detail-ifytxtex5079182.shtml (accessed October 25 2022).

- Fast Company (2020, March 10),“The 10 Most Innovative Chinese Companies of 2020”, available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90457942/china-most-innovative-companies-2020 (accessed October 25 2022).

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2020), “Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report”, available at: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2019-2020-global-report (accessed October 25 2022).

- Gao, J. and Mu, R. (2021), “Mass Entrepreneurship and Mass Innovation in China”, Fu, X. (Ed.), McKern, B. (Ed.), Chen, J. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of China Innovation, Oxford University Press, New York: pp. 254–271.

- Garnaut, R., Song, L., Yao, Y., and Wang, X. (2012), Private Enterprise in China, The Australian National University E-Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Hamnett, C., Hua, S., and Liang, B. (2019), “The Reproduction of Regional Inequality Through University Access: The Gaokao in China”, Area Development and Policy, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 252– DOI: 10.1080/23792949.2018.1559703

- Handley, L. (2017, November 8), “Zhang Xin: The Woman who Built Beijing”, CNBC, available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/11/from-factory-worker-to-real-estate-billionaire-soho-chinas-zhang-xin.html(accessed October 25 2022).

- Lardy,N. (2014), Markets over Mao: The Rise of Private Business in China, Peterson Institute for International, Washington, DC.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021), “China Statistical Yearbook 2021, 1-8 Number of Corporate Enterprises by Region and Status of Registration (2020)”, available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexeh.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- National Eastern Tech-Transfer Center (2019), “National Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Week 2019 is Hot to Start”, available at: https://www.netcchina.com/en/archives/8467 (accessed October 25 2022).

- Nie, W., Xin, K., and Zhang, L.(2009), Made in China: Secrets of China’s Dynamic Entrepreneurs, John Wiley and Sons (Asia), Singapore.

- Marwan, S. (2022, October 18), “Report: Gen Z Fast Fashion Comes at an Inhumane Cost to SHEIN Workers”, Fast Company, available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90797387/gen-z-fast-fashion-comes-at-an-inhumane-cost-to-shein-workers (accessed October 25 2022).

- McCorvey, J.J. (2018, March), “How VIPKid CEO Cindy Mi Made Education a Universal Language”, Fast Company, available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/40525523/how-vipkid-ceo-cindy-mi-made-education-a-universal-language (accessed October 25 2022).

- Mei, Q. (2022), “Fortune Favors the State-Owned: Three Years of Chinese Dominance on the Global 500 List”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, available at: https://www.csis.org/blogs/trustee-china-hand/fortune-favors-state-owned-three-years-chinese-dominance-global-500-list (accessed October 25 2022).

- Murray, A. and Meyer, D. (2020, August 10), “The Fortune Global 500 is now more Chinese than American”, Fortune, available at: https://fortune.com/2020/08/10/fortune-global-500-china-rise-ceo-daily/ (accessed at October 25 2022).

- OECD (2022), “China Economic Snapshot. Economic Forecast Summary (June 2022)”, available at: https://www.oecd.org/economy/china-economic-snapshot/ (accessed October 25 2022).

- Reuters (2021a, April 29), “Factbox: How China’s Regulatory Crackdown has Reshaped its Tech, Property Sectors”, available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/education-bitcoin-chinas-season-regulatory-crackdown-2021-07-27/ (accessed October 25 2022).

- Reuters (2021b, August 7), “VIPKID to Stop Selling Foreign-based Tutoring to Students in China”, available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/vipkid-stop-selling-foreign-based-tutoring-students-china-2021-08-07/(accessed October 25 2022).

- Schaper, A.-K. and Fischer, D. (2021), “Does Gender Matter for the Entrepreneurship Fairy Tale? An Analysis of Chinese Unicorn Start-ups”, CBE Research Note, 2, University of Würzburg, Würzburg.

- Shleifer, E. and Kologrivaya K. (2021, June 29), “Out of Lockdown: China’s Edtech Market Confronts the Post-pandemic World”, South China Morning Post, available at: https://www.scmp.com/tech/tech-trends/article/3139056/out-lockdown-chinas-edtech-market-confronts-post-pandemic-world (accessed October 25).

- Startup Genome (2022), “The Global Startup Ecosystem Report (GSER 2022)”, available at: https://startupgenome.com/reports/gser2022 (accessed October 25 2022).

- Startup Genome (2022), “Beijing”, available at: https://startupgenome.com/ecosystems/beijing (accessed October 25 2022).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2015), “国务院关于大力推进大众创业万众创新若干政策措施的意见 [The State Council’s Opinion on Promoting Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy Measures]”, available at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/16/content_9855.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2018), “中共中央政治局委员、国务院副总理刘鹤就当前经济金融热点问题接受采访” [Interview with Liu He (Member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Vice Premier of the State Council) on the Current Economic and Financial Issues], available at: http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2018-10/19/content_5332515.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2022), “China Holds National Mass Entrepreneurship, Innovation Week”, available at: http://english.www.gov.cn/news/photos/202209/19/content_WS6327c545c6d0a757729e02ef.html (accessed October 25 2022).

- Times Higher Education (2022), “World University Rankins 2022”, available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2022 (accessed October 25 2022).

- Tsinghua (2022), “Tsinghua X-Lab”, available at: http://www.x-lab.tsinghua.edu.cn/en/ (accessed October 25 2022).

- Tsinghua School of Economics and Management (2022), “Tsinghua SEM-elerator”, available at: https://www.sem.tsinghua.edu.cn/en/Programs/Tsinghua_SEM_X_elerator.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- VIPKID (2020, June 24), “17 Questions with EdTech CEO of the Year, Cindy Mi”, available at: https://blog.vipkid.com/17-questions-with-edtech-ceo-of-the-year-cindy-mi/ (accessed October 25 2022).

- VIPKID (2022), “About us”, available at: https://www.vipkid.com/mkt/about-us (accessed October 25 2022).

- World Bank (2022), “GDP Growth (Annual in Percent) – China”, available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=CN (accessed October 25 2022).

- Xinhua (2020, October 15), “Chinese Premier Stresses Innovation, Entrepreneurship to Drive Growth”, available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexeh.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- Xinhua (2018, October 10), “2018 National Mass Innovation and Entrepreneurship Week Held in Beijing”, available at http://english.scio.gov.cn/chinavoices/2018-10/10/content_65575935_3.htm (accessed October 25 2022).

- Zaha Hadid Architects (2022), “Leeza SOHO”, available at https://www.zaha-hadid.com/architecture/leeza-soho/(accessed October 25 2022).

- Zamora, G. (2022, May 4), “The 10 Richest Self-made Women in the World”, Forbes, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/gigizamora/2022/04/05/the-10-richest-self-made-women-in-the-world/?sh=3618c7a36c25 (accessed October 25 2022).

- Zenglein, M. J. and Holzmann, A. (2019), “Evolving Made in China 2025. China’s Industrial Policy in the Quest for Global Tech Leadership”, Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) Papers on China, No. 8, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/MPOC_8_MadeinChina_2025_final_3.pdf.

- Zhang, C. (2019), “How Much do State-owned Enterprises Contribute to China’s GDP and Employment?”, World Bank, Washington, DC, Working Paper, available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32306.

- Zitelmann, R. (2019, September 30), “State Capitalism? No, the Private Sector was and is the Main Driver of China’s Economic Growth”, Forbes, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rainerzitelmann/2019/09/30/state-capitalism-no-the-private-sector-was-and-is-the-main-driver-of-chinas-economic-growth/?sh=12db4c2227cb (accessed October 25 2022).