Nicolas Mues, University of Siegen

Abstract

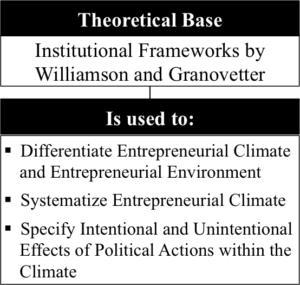

Recent election results and debates in Germany increasingly create uncertainties in society, but also among entrepreneurs. The perceived instability of the political systems and the lengthy coalition negotiations make it difficult for entrepreneurs to foresee the framework conditions for their future actions. This could hinder entrepreneurs‘ innovative strength. From an institutional perspective, these political obstacles seem to have an impact above all on the so-called hard facets of environmental conditions, for example on laws or on supporting measures from governments. But in addition to these hard or formal requirements, there are also numerous influencing factors that are difficult to grasp. These are subjective, soft framework conditions. These framework conditions are also significantly influenced by political actors. On the one hand, there are intended actions by political actors that affect entrepreneurs. These effects are easy to observe for those affected and researchers because they are codified and visible. On the other hand, the actions of political actors that are not directly aimed at entrepreneurs can also have an impact on these entrepreneurs. These effects are usually not obvious and can therefore be called „soft“. Hence, these effects occur mostly on a perceived level. One can speak of „Entrepreneurial Climate“. In contrast to the term „Entrepreneurial Environment“, this climate encompasses especially felt framework conditions. However, there are no clear conceptualizations of the „Entrepreneurial Climate“. Not only should the idea of the „Entrepreneurial Climate“ be defined, but also inserted into the entrepreneurial process, going from the idea generation to the commercialization, in order to be able to recognize possible answers of the entrepreneur to political actions. As these framework conditions are decisive for the success of the company, this entry creates a systematization of the entrepreneurial climate and the actions of political actors within this framework. Essential models of institutional theory by Williamson and Granovetter institutional theory serve as the basis for this systematization. In addition, various distinctive perspectives are used to investigate the entrepreneurial climate.

Entrepreneurs as the Driving Force of an Economy within Complicated Political Conditions

In recent times, the political climate in Germany is becoming harsher. Coalition negations take several months and end in unsatisfactory alliances. Although German federalism is almost known as a synonym for stability and the government coalitions are considered to be extremely durable in comparison to other european countries, even here the reigning coalition is always on the brink of collapse (Rosemann 2000). The current coalition of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) and the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) is only an alliance of convenience. In Saxony, a federal state of Germany, a three-party alliance is formed under Prime Minister Michael Kretschmer, after the former big parties suffered heavy losses in the election. In Thuringia, another German federal state, the government formation was also chaotic. One can also look at the international level, where relations cool down. All these controversies create a frustrating picture for society as well as economic actors. It is not just the coalition negotiations that create this picture. The culture of debate in Germany also appears to be deteriorating. These impressions lead to a rejection of politicians by society. Government approval ratings are poor. The business climate in the German economy has also been rated weaker for years, as the IFO Business Climate Index shows, an important indicator of economic development. While large companies may have enough reserves to prepare for multiple scenarios, smaller companies will find it more difficult to act strategically. This also hinders entrepreneurial activities. Political circumstances are an important element of the entrepreneurial climate and can promote, complicate or even prevent the establishment of young companies. Political actions are a good example that intentional and unintentional effects on entrepreneurs can arise. This is also evident in the entrepreneurial climate, which, in contrast to the environment, comprises rather soft, informal or perceived circumstances. However, this makes the intended systematization all the more difficult.

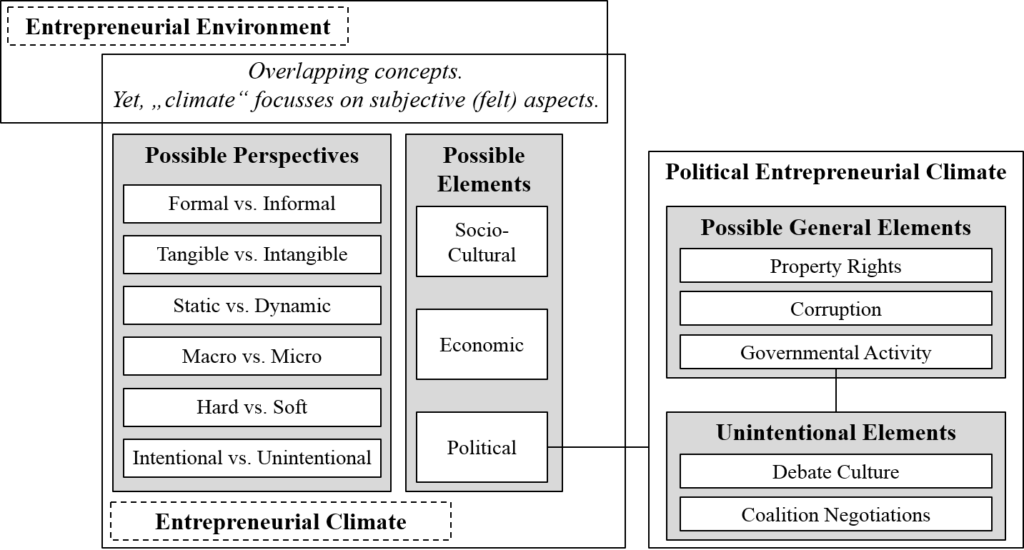

Thus, entrepreneurial climate, in this article, is considered as the combination of environmental conditions for entrepreneurs, with a special focus on soft factors and thus also on the subjective perception of the entrepreneurs. This perception arises primarily in the local environment. Entrepreneurial environment, on the other hand, is broader and focuses more on the infrastructure and the legal framework.

Entrepreneurship is considered an important factor, perhaps the most important factor in a country’s economic development (Aidis et al., 2012). Therefore, more and more scientists are dealing with entrepreneurship and a supportive environment (Tolbert, David, & Sin, 2011). While initially the personality traits of the entrepreneurs were in the foreground, in recent years, more focus has been placed on the institutional framework. Institutional theory in particular is suitable for in-depth investigation of the relationship between the actions of political actors and the reactions of entrepreneurs. However, many actions by politicians are not directly aimed at the business environment, but they have an indirect impact on the perception by entrepreneurs. It is therefore important to use the entrepreneur’s process as a further basis. One can distinguish an entrepreneur’s process into the following phases: A) The idea for a business model is developed or an opportunity is seized. B) The decision is made to pursue the idea further. C) The search for the necessary resources begins. D) Then the company starts its daily operational business. E) This is followed by the continuous expansion of the company and the focus on economic success (Peters, Ric, & Sundararajan 2004). This process is embedded in the institutional environment. Regarding this integration, institutional theory examines how social norms and basic social assumptions affect individual action (Tolbert, David, & Sine 2011). Since such norms often appear in the form of laws or political principles, the influence of political actions should not be underestimated. However, the concept of entrepreneurial climate has not yet been clarified, especially with regard to the importance of politicians. The main difficulty is the subjective and subconscious nature of the effects of the entrepreneurial climate.

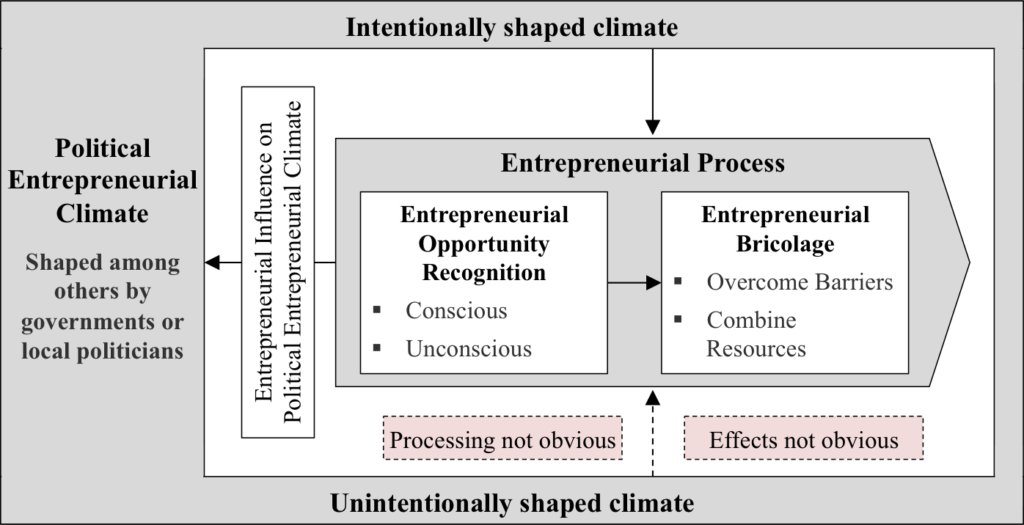

Therefore, this article is intended to help to define and systematize entrepreneurial climate. It is to be described which elements belong to the entrepreneurial climate and specifically it should be clarified how the actions of political actors are to be classified. For this, it is necessary to conceptualize the entrepreneurial climate as a whole and to further break down governmental action. Building on the views of institutional theory, there are multiple methods of dividing or hierarchizing political actions that affect entrepreneurs. However, given the current political debate culture, it is instructive to examine how actions by political actors that are not directly targeted at these entrepreneurs affect entrepreneurial behavior. A distinction is thus made between the intentional and unintentional effects of political action. This has a lot to do with the subjective perception of the entrepreneur, which is why concepts of the entrepreneurial process should also be integrated. This way, these insights will create an extension of the application of institutional theory to entrepreneurs. The approach to specify the unintentional effects of political actors within the entrepreneurial climate is depicted in Figure 1.

The Institutional Perspective as a Useful Lense to Systematize the Entrepreneurial Climate

Using Williamsons and Granovetters Essential Models to Better Understand the Entrepreneurial Climate

In economic sciences, the entrepreneur and the impact of his work were relevant early on. Already in the early twentieth century, Schumpeter and Knight investigated how entrepreneurial success came about (Bjørnskov & Foss 2008) and mainly highlighted personal characteristics of entrepreneurs. Gradually, however, other theoretical foundations provided important insights. The more complex the environment became, the more ideas from institutional theories were used (Veciana & Urbano 2008). Political support for entrepreneurs also came into focus. For about two decades now, there has been a noticeable integration of institutional theory and entrepreneurial behavior (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li 2010). The basic idea of institutional theory in this context is that groups or individuals often strive to be successful by adapting better to rules and norms (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li 2010).

Although institutions that impact society and entrepreneurs often develop over long periods of time, they are essentially seen as more or less formalized human-made norms. Their purpose is mostly to create order and reduce uncertainty. Institutional norms are conveyed through cultures, structural routines, but also through unconscious processes. Accordingly, there are obvious and unconscious types in the transmission of institutions and the related perception and further processing.

A lot of work has already systematized and hierarchized institutions. Such subdivisions are useful to examine which elements of institutions trigger which effects in the corporate environment and how entrepreneurs can react to them. Connections to the entrepreneurial process can also be established in this way. One basic idea of institutions is that they consist of a regulatory, a normative and a cognitive pillar (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li 2010; Scott 2013). The regulatory pillar is made up of political regulations and industrial agreements. The normative pillar refers to behaviors preferred by society. The cognitive pillar in turn relates to the individual and subjective perception. This is particularly important in this context, since it has so far hardly been examined how, for example, the political climate has an indirect and unintentional effect on entrepreneurship.

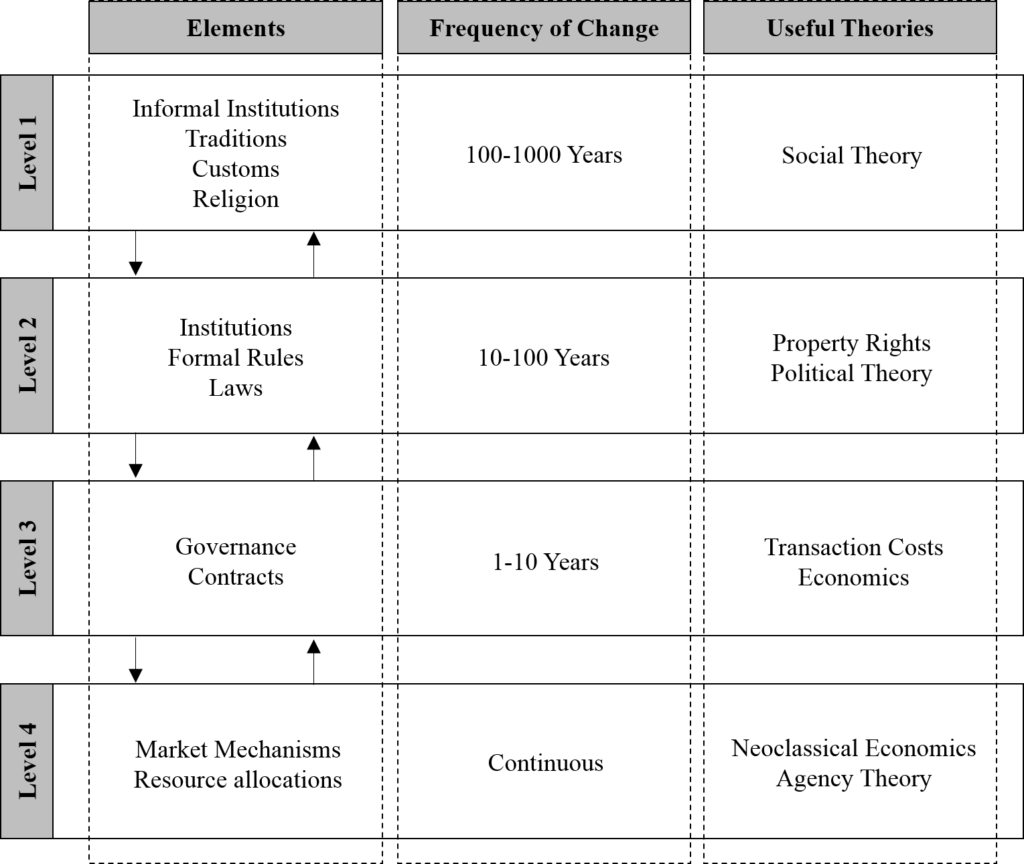

A second fundamental system of institutions, which is helpful in this context, comes from Williamson (2000) and is depicted in Figure 2.

He creates a hierarchy of four institutional levels and also explains the creation of these levels. The top level describes the social embeddedness, which is characterized by traditions or religions and therefore has the greatest influence. The second level, called „institutional environment“, is characterized by formal rules such as laws. The government is decisive here. Therefore, the political theory is significant at this level. The two lower levels, governance structures and market mechanisms, are less influential. This level model was then transferred to entrepreneurship theory. Bylund and McCaffrey (2017) call the second level „Rules of the Game“. The government is a main player on this level. At this level, political uncertainty is particularly dangerous due to policy changes and the resulting unpredictability of legal requirements or support measures. Entrepreneurs can have different answers to this. They can try to adapt, they can simply fail or they can try to influence the political actors. Accordingly, the relationship between politics and entrepreneurship is two-sided.

Williamson’s framework is not only relevant in theory, but also in practice to better understand the entrepreneurial environment. In Germany, bureaucracy is often seen as a barrier, which would be classified on the second level. However, surveys also show that there can apparently be a social rejection of innovation in Germany (Jansen 2019). This takes place on the first level. Williamson also shows how long it can take for the levels to change. The top two levels take a long time to change. However, local characteristics can act as compensation. For example, Hamburg has developed into a hotspot in recent years. The basic values of society also differ from city to city. Hamburg is seen as more binding and more sustainable than, for example, Berlin. But political actors are just as important. Hamburg’s mayor also emphasizes that Hamburg is more open and enthusiastic than Berlin (Jäger 2018). In addition, an innovation-friendly, proactive and participative cluster policy was introduced in Hamburg and cooperation between startups and universities was increased. For the upcoming election in Hamburg, the parties have explicitly highlighted reducing bureaucracy, a better legal framework and the creation of a welcoming culture for foreign specialists. This shows how local initiatives compensate for national barriers.

Another basic idea of social analysis is the distinction between social micro and macro levels. This distinction goes back to Granovetter (1985). Estrin et al. (2013) explain that the micro level, especially the local environment, can not only alleviate, but compensate for errors on a larger (macro) level. Thus, it can be expected that a distinction must be made between state and local political activities, which, however, also have interdependencies.

It is described that institutions should create order. But changes in the institutional system can also lead to uncertainty. It is therefore important to understand how entrepreneurs create their expectations. This can happen in a conscious or unconscious way. Subsequently, entrepreneurs carry out a corresponding action. It is also pointed out that entrepreneurs rarely have complete certainty when it comes to building expectations (Sarasvathy et al. 2003). In addition, the entrepreneur’s knowledge that it is essential in the formation of expectations is not tangible and therefore such processes are often subconscious. Sarasvathy et al. (2003) emphasize that institutions, in the sense of routines, can lead to stability. However, they can also cause instability if there are sudden changes. This raises the question of how the entrepreneur should behave or respond.

From Opportunity Recognition to Exploitation: The Entrepreneurial Process Embedded in the Institutional Climate

There is general agreement on the arrangement of the entrepreneurial process (Peters, Ric, & Sundararajan 2004). If one uses the institutional theory to investigate entrepreneurial behavior, one step has to be added. The entrepreneurial process now begins with the creation of an institutional framework as an upstream step and a starting point as can be seen in Figure 2. The government plays the central role here, especially with regard to formal elements of the environment. However, government action can of course also influence the informal framework. As a next step, the entrepreneur creates his expectations. This step is called „Entrepreneurial opportunity recognition“ and describes the ability to recognize opportunities in which new ideas can be introduced through new development processes (Phillips & Tracey 2007). However, it emphasizes that opportunities do not simply exist, but that entrepreneurs can create them themselves. This fits with the view that entrepreneurs not only adapt to institutions, but can also influence them. Formal institutions are much easier to perceive, for example through laws, judicial decisions or competitive regulations (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li 2010). However, this is not the case with indirect influences. A distinction must be made as to how the entrepreneur interprets these institutions and the corresponding changes. Institutions can be interpreted as limitations or as supportive conditions (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Li 2010). Finally, the entrepreneurs aims to exploit the recognized opportunity. Phillips and Tracey (2007) explain that entrepreneurial success depends above all on a skill called „bricolage“. This skill is characterized on the one hand by the rejection of restrictions which could be created by institutional requirements or institutional uncertainty. On the other hand, “bricolage” includes the new combination of resources, which can also be valuable in the future. The question here is whether the entrepreneur can also transcend unconscious boundaries that can be triggered by political instability.

The Need for Further Integration of Institutional Ideas and the Entrepreneurial Process

In recent years, there is greater integration of institutional theories and concepts of entrepreneurial characteristics. As Bruton, Ahlstrom & Li (2010) explain institutional theory is increasingly used to investigate which influencing forces from the environment affect entreprenurs in their actions. Institutional theory thus complements, for example, the resource based view. Regarding the effects of institutions on entrepreneurs, there are still large gaps with regard to the indirect or unconscious effects on the entrepreneurial climate. The distinction between formal and informal institutions is a starting point. However, in order to research the unintended effects of political action, a deeper understanding of cognitive processes of entrepreneurs is necessary, because often it is rather a feeling than a tangible assessment that makes the entrepreneur act (van der Zwan & Thurik 2011). As a framework, a distinction must also be made between the general economic environment and entrepreneurial climate. Granovetter’s ideas about social embeddedness state that there are interdependencies here. This creates the picture of a complex network of effects that has so far been neglected. However, the discussed theories provide a good basis. Accordingly, the planned concept refers to the cognitive pillar of institutions. With regard to the model of social analysis by Williamson, the topic has to be classified on the second level.

Defining the Entrepreneurial Climate

V2 The Entrepreneurial Climate and its Major Elements

In order to create a precise concept for the outlined problem, the concept of the entrepreneurial climate and the role of politicians and their various actions within the climate must be examined in more depth. The few publications that offer a definition of the entrepreneurial climate do not always formulate clear distinctions from the general economic environment. Roxas et al. (2007) define the local entrepreneurial climate as the compilation of tangible and intangible institutional factors that affect entrepreneurs in a geographically and politically defined region. Regarding this, the distinction between macro and micro levels of Granovetter exhibits practical relevance. „Climate“ as a term has to be distinguished from the „environment“, because the climate includes tangible circumstances such as infrastructure or financial support as well as felt, elusive circumstances. This includes, for example, the perceived acceptance of corporate failures in local society or the attention that entrepreneurs receive in the local press (Goetz & Freshwater 2001). This makes the cognitive pillar relevant again.

The interplay between politics and the subconscious perception of the environment by entrepreneurs can be illustrated using the example of Christian Lindner. Lindner, who is now head of the FDP (Free Democratic Party), failed in 2001 with a software startup. During a speech on the founding culture in Germany in the state parliament in 2015, there was an interjection from a SPD MP who made fun of Lindner’s failure as an entrepreneur. Lindner then began an angry speech in which he said that failure in Germany is still a stigma, that a change in mentality is needed and that there are still many in Germany who are afraid of globalization and are risk-averse (Basel 2016). Suitable for this article, Lindner asked at the end: „What impression does such a stupid interjection like yours make on someone willing to start up?“ (Lindner 2015). This is an exact example of how politicians‘ behavior could unintentionally have a big impact on entrepreneurs.

The different effects of economic and entrepreneurial climate as distinct concepts were also described by van der Zwan, Verheul and Thurik (2011). The economic environment provides impetus or creates barriers. However, it is above all the entrepreneurial climate, which means the subjective impression of the conditions, that makes the entrepreneur convert his ideas into actual business models (Arenius & Minniti 2005). With regard to Granovetter’s ideas one could differentiate between regional and national entrepreneurial climate. The framework conditions are mostly divided into formal and informal circumstances. Formal institutions that are important for entrepreneurs are among others written policies, laws and regulations. In addition, one counts political and economic guidelines as well as contracts among this category (Roxas et al. 2007). Another term for this could also be „hard institutions“. In contrast, there are formal institutions such as traditions, behaviors, moral principles or religious attitudes. These are conventions that are rarely officially sanctioned, but disregarding them can lead to a major disadvantage for entrepreneurs. Yet, current discussions of entrepreneurial climate are rather lists, which are also not complete and can be expanded. One of these lists, developed by Goetz and Freshwater (2001) includes for example the support from the mayor, a high degree of cooperation with the educational institutions or good local financing options. Shane, who sets up a concept for a productive environment for entrepreneurs, stresses the role of politics. According to him, there are three pillars of the entrepreneurial climates: socio-cultural, economic and political influences. In addition to that, the distinction between hard and soft factors is particularly interesting (Goetz & Freshwater 2001). The authors include aspects such as whether entrepreneurial success is celebrated, whether local newspapers often cover entrepreneurial successes and whether there is acceptance in case of entrepreneurial failures in the local environment. This underlines the distinctive feature of „Climate“ and „Environment“. Intuition and perceived support are of great importance in entrepreneurial climate. The method of measurement for these soft factors used by Goetz and Freshwater is less convincing. The authors mainly capture the influence of hard factors on entrepreneurial success and explain that the residual reflects the effect of soft factors. On the one hand, this makes it clear that entrepreneurial climate has a lot to do with intangible aspects and, on the other hand, that this makes it difficult to create a concrete measurement.

It was found that the entrepreneurial climate differs from the environment because it depends heavily on subjective and intuitive impressions. Therefore, a distinction between hard and soft institutions seems reasonable. The idea of soft and hard factors exhibits clear overlaps with the distinction between formal and informal institutional conditions.

Intentional and Unintentional Effects of Political Actors on Entrepreneurs

Concerning governmental or political actions towards the entrepreneurial climate, we are on the second level in the Williamson model. The government and other political actors have great power on this level. After the entrepreneurial climate has been outlined and differentiated from the general economic environment, the role of political actors in this context is now to be discussed. Shane (2003) explains that the political component in entrepreneurial climate includes aspects such as freedom, property rights and the decentralization of power. Estrin et al. (2013) refer to similar components. According to them, the classification in Williamson’s model is particularly important in order to be able to assess the possible reactions of the entrepreneurs. They list three aspects of the political entrepreneurial climates: corruption, property rights and government activity. Aidis et al. (2012) explain that the last aspect can have conflicting effects. An active state could better protect property rights, but it could also be a competitor to entrepreneurs, demand higher taxes or reduce incentives for entrepreneurs through social policy. Yet, the unique features of governmental action compared to other political influences in the entrepreneurial climate are seldom determined. This drawback can also be found in the explanations of Bjørnskov and Foss (2008), who offer a detailed list of political actions (including „size of the government“, „administrative complexity / bureaucracy“ or „political freedom“ „), but do not define separation of governmental activities to aspects such as corruption or crime. However, a distinction made by Estrin et al. (2013) is helpful for a better conceptual understanding of the topic. They describe that, on the one hand, the government is limited by rules (constitutional institutions) and that on the other hand the government can create institutions itself. Roxas et al. (2007) argue in a similar way. They differentiate between contextual and dynamic political framework conditions for entrepreneurs. While contextual framework conditions are comparatively stable and could refer to traditions or the constitution, political legislative initiatives or political programs are rather dynamic.

While formal framework conditions are often the result of deliberate actions by governments, informal conditions are rather created through unintentional actions. Since the creation and impact of informal components of the entrepreneurial climate are difficult to grasp, they have so far been neglected in scientific publications. According to Bruton, Ahlstrohm and Li (2010), the crucial function of informal institutions is to fill the gaps left within formal institutions. Here, it is important to differentiate between the terms “environment“ and „climate“ regarding entrepreneurs. The “climate” emphasizes the individually perceived conditions. The difficulty here is that subjective, intangible factors are not easy to observe. An important source that influences the perceived component of the climate are unintentional effects from politics. For example, lengthy and complicated coalition negotiations lead to uncertainty and can worsen the climate. More radical parties and polarizing statements can also make entrepreneurs act more cautiously. Due to political disputes, entrepreneurs can no longer be sure that the general conditions remain stable.

The unintended effects of political actors on entrepreneurs therefore arise from the actions of politicians which are not aimed at promoting entrepreneurs but which nevertheless have an indirect influence on the entrepreneurial climate. However, how this influence works has not yet been clarified.

A First Integration of Unintended Political Actions within an Institutional Perspective of the Entrepreneurial Climate

Considering the polarized atmosphere in international and German politics, it can be expected that the perceived assessment of the situation by the entrepreneurs has drastically changed, too. Since this is an indirect and unintentional connection, one can speak of an emotional and subjective effect. It can be assumed that this effect is not insignificant. To examine the relationship between the political and the entrepreneurial climates, however, a precise definition and classification of the term is necessary.

The entrepreneurial climate can be distinguished from the general economic environment since it stresses the perceived circumstances and the subjective component of the institutional framework conditions. It is helpful to use different perspectives and distinctions. One can distinguish, among other perspectives, between formal and informal, hard and soft or rigid and dynamic institutional conditions. Although it has already been recognized that political actors play an important role in the entrepreneurial climate, the discussed effects are mainly intentional effects. Therefore, a new distinction is conceived: intentional and unintentional. In particular, the debate culture and the duration and complexity of coalition negotiations or political decision-making processes can be classed as these unintentional effects. The distinction between the terms „environment“ and „climate“ as well as useful perspectives and proposed elements of the entrepreneurial climate are depicted in Figure 3. This way, a starting point for a deeper understanding of unintentional effects of political actors on entrepreneurs has been created. This gives rise to important scientific and practical questions. One has to search for other unintentional influences and how these relationships work. In addition, the models by Williamson (2000) and Bylund and McCaffrey (2017) can be used to recognize how entrepreneurs can react to political actors and their behavior. This area of research is becoming increasingly important, as is shown by the increasing importance of institutional entrepreneurship.

References

Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. M. (2012). Size matters: entrepreneurial entry and government. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 119-139. doi: 10.1007/sl 1 187-010-9299-y.

Arenius, P. & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233-247. doi: 10.1007/slll87-005-1984-x.

Basel, Nicole (2. September 2016): Christian Lindner übers Scheitern. “Es hieß schnell: Die waren unfähig.“ Retrieved from: https://www.impulse.de/management/unternehmensfuehrung/christian-lindner-uebers-scheitern/3288345.html

Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. J. (2008). Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence. Public Choice, 134(3-4), 307-328. doi: 10.1007/s11127-007-9229-y.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.-L. 2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34(3), 421-440. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x.

Bylund, P. L., & McCaffrey, M. (2017). A theory of entrepreneurship and institutional uncertainty. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 461-475. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.006

Estrin, S., Korosteleva, J., & Mickiewicz, T. (2013). Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations?. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 564-580. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001.

Goetz, S. J., & Freshwater, D. (2001). State-level determinants of entrepreneurship and a preliminary measure of entrepreneurial climate. Economic Development Quarterly, 15(1), 58-70. doi: 10.1177/089124240101500105.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510. doi: 10.1086/228311.

Jäger, Mathias (13. September 2018): Gründerfrühstück mit Peter Tschentscher: Wie sexy ist Hamburg? Retrieved from: https://www.hamburg-startups.net/gruenderfruehstueck-mit-peter-tschentscher-wie-sexy-ist-hamburg/

Jansen, Jonas (5. August 2019): Deutschlands Gründer leiden unter der Bürokratie. Retrieved from: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/digitec/start-up-gruender-in-deutschland-leiden-unter-der-buerokratie-16317674.html

Lindner, Christian (2015): Rede im Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen. In: Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen (Hg.) 2015: 78. Sitzung Plenarprotokoll 16/78 (29.01.2015), 7924-7931. URL: https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument/MMP16-78.pdf.

Minniti, M. (2008). The role of government policy on entrepreneurial activity: productive, unproductive, or destructive?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 779-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00255.x.

Peters, L., Rice, M., & Sundararajan, M. (2004). The role of incubators in the entrepreneurial process. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 83-91. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011182.82350.df.

Phillips, N., & Tracey, P. (2007). Opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial capabilities and bricolage: connecting institutional theory and entrepreneurship in strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5(3), 313-320. doi: 10.1177/1476127007079956.

Rosemann, M. (2000). Restoration and Stability: The Creation of a Stable Democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany. In: J. Garrard, V. Tolz & R. White (Eds.), European Democratization since 1800 (pp. 141-162). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Roxas, H., Lindsay, V., Ashill, N., & Victorio, A. (2007). An institutional view of local entrepreneurial climate. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 3(1), 1-28. doi: 10.3860/apssr.v7i1.113.

Sarasvathy, S.D., Dew, N., Velamuri, S.R., & Venkataraman, S. (2003). Three views of entrepreneurial opportunity. In: Z.J. Acs & D.B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 141-160). Boston, MA: Springer.

Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Shane, S. A. (2003). A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Smallbone, D., Welter, F., Voytovich, A., & Egorov, I. (2010). Government and entrepreneurship in transition economies: the case of small firms in business services in Ukraine. The Service Industries Journal, 30(5), 655-670. doi: 10.1080/02642060802253876.

Tolbert, P. S., Robert J. D., & Wesley D. S. (2011). Studying choice and change: The intersection of institutional theory and entrepreneurship research. Organization Science, 22(5), doi: 1332-1344. 10.1287/orsc.1100.0601.

van der Zwan, P., Verheul, I., & Thurik, R. (2011). The entrepreneurial ladder in transition and non-transition economies. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 1(2), Article 4. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9334-7

Veciana, J. M., & Urbano, D. (2008). The institutional approach to entrepreneurship research. Introduction. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(4), 365–379. doi: 10.1007/s11365-008-0081-4.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595-613. doi: 10.1257/jel.38.3.595.