Karoline Braun, external doctoral student at the Chair of Human Resource Management and Organization, University of Siegen

Contact: karoline.braun@uni-siegen.de

Abstract

As a result of the Corona crisis, many workers are being thrown back into traditional conditions and are experiencing a clear sense of foreign domination. Especially in such times of restrictions, the question of possibilities of co-determination in organizations arises more intensively than usual. Beyond that, for many people the restrictions lead to salary losses or even job loss, so that they necessarily have to deal with other, new possibilities to earn a living. From the point of view of companies, too, it seems to make sense to think about leadership, participation and entrepreneurship in order to be able to survive crises better – or at all.

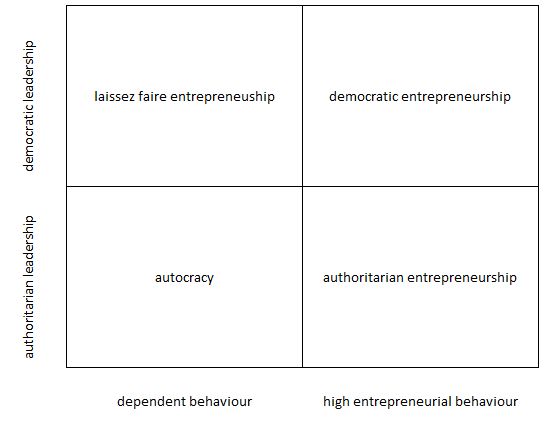

This blog entry from the field of modern entrepreneurship research offers an innovative combination of democracy and entrepreneurship. It is particularly applicable to organizations in the fields of politics, economics and education, but other areas are also conceivable. The developed four-field matrix can be applied from the point of view of employees and entrepreneurs and allows considerations for both new organizations to be founded and for already existing organizations. Users can see from the perspective of the entrepreneur whether a high or low level of democracy seems to make sense for the organization and which aspects of co-determination should be taken into account.

Today there are countless organisations that cannot ensure their continued existence in the long term due to a lack of applicants or unmotivated employees. The situation is influenced by Generation Z, which is currently entering the labour market and has completely different demands on entrepreneurs than its predecessors, as well as by globalization and digitization, which bring additional dynamics into the everyday life of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs are strongly advised to consider current developments in management and not to leave the founding or continuation of their company to chance.

Everyone talks about “democracy”. And often not only democratic processes of governance are meant. Whether it’s about democratic companies or democratic leadership and participation, the term is used inflationary. Every possibility of co-determination in companies, no matter how small, is immediately named and advertised as a democratic term. The reactions to this democratisation in the economy vary widely and are by no means all positive: some people welcome this development and consider participation to be important in general, while others are sceptical in principle, as democratic processes are considered too time-consuming and too complicated. Such an undifferentiated approach cannot be effective. Both, a fundamentally negative attitude and an unquestioned positive attitude towards democratic processes, seem inappropriate, and therefore, democracy as a principle in the context of companies should be critically examined in this blog.

And „entrepreneurship“? Some readers know that there is a whole branch of science behind it, for others it is a completely new foreign word. In any

case, it is a technical term that is known in practice from the start-up scene and is being researched and further developed in theory by scientists. Due to the many different scientific disciplines and the many different researchers, the understanding of the term is enormously broad and the content can vary considerably. Despite much theoretical research, a successful entrepreneurship in practice does not always have to do with theoretical scientific considerations. There are numerous examples where people with luck and a brilliant idea started out in a garage and gradually grew from a start-up into a successful company. In the course of this blog entry, I will show you more about modern entrepreneurship research in a wide variety of fields.

And there is more: by the title of this blog entry, I promise above all a connection between democracy and entrepreneurship that is not obvious at first glance. There is also no abundance of academic literature on „democratic entrepreneurship“. Even this brief introduction to the blog entry therefore shows that it is worth taking a closer look here to find out what democratic entrepreneurship is. I describe and define the terms „democracy“ and „entrepreneurship“ one after the other. Finally, I will give a hint to decide in which case „democratic entrepreneurship“ can be a recommendable way for modern entrepreneurship.

Democracy!

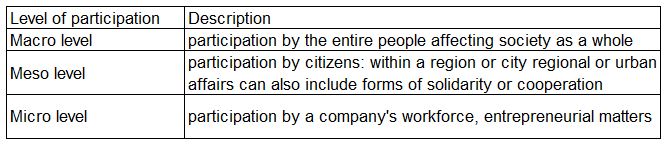

In general, democracy has something to do with formalized procedures for free and equal participation (e.g.: Vorländer 2003). However, depending on the specific context, this participation takes very different forms and also relates to very different areas of people and objects of participation. For a start and following Bergmann, Daub & Özdemir 2019, three levels of participation can be distinguished:

The macro level deals with general social or economic issues affecting the state, society or the economy in general. Through elections, the people can elect their representatives whose task it is to act in the interests of the voters in political institutions and decision-making processes.

The meso-level deals with regional or urban issues, which may also include forms of solidarity and cooperation. The people living in the city or region are also involved through the election of political representatives whose task it is to represent the interests of the people in the city or region.

At the micro level, it is about entrepreneurial issues. The workforce is involved, e.g., in decisions on profit-sharing or restructuring.

The three levels are summarised in the following table:

Further confusion is caused by the fact that the term „democracy“ is not only used differently within the three levels described. Moreover, it is also understood differently in different research areas. For a better understanding of the term, the three areas of science in which the concept of democracy has become increasingly important are explained below: politics, economics and education.

Democracy and politics

The word „democracy“ is often intuitively associated with politics. In this case it is about electoral processes and elections as well as a free democratic basic order of a country. In this form of governance, the people exercise state power through elected representatives (Bundestag without date). There are repeated discussions about whether citizens should be more involved, e.g. through referendums at the federal level (Mehr Demokratie e.V. 2020). There are many debates about whether individual parties in a democracy that do not support a basic democratic order should be banned (so far without success in the sense of a ban, e.g. for the German NPD; (Bundesverfassungsgericht 17.01.2017)).

The understanding of the concept of democracy as a form of governance changes considerably over time: before the French Revolution, democracy was only one of several possible forms of governance. The Revolution led to enormous social upheavals and democracy gained in importance. The reason for this was the desire for more equality and participation, which in turn led to democracy becoming and remaining the only desirable form of governance (more informations e.g. here: Kuhn 2018).

In terms of the division into different levels according to Table 1, democracy in politics mainly belongs to the macro and meso levels.

Democracy and economics

Business studies are increasingly concerned with the study of democratic governance, and there is also an overlap with concepts of holocracy and New Work. Holocracy is a concept from the USA, which – instead of the traditional personal authoritarian leadership – is about a lot of transparency and participation of the workforce in decisions (more information e.g. here: Robertson 2015). New Work is another concept that turns away from conventional wage labour and focuses on a working world that has been fundamentally changed by digitalization and globalization. It promotes in particular the independence of employees, freedom and participation in the community (more information e.g. here: Robertson 2015; Bergmann 2004).

Although the idea of democratic corporate governance has only been booming for a few years, the first roots of corporate democracy in Germany can be traced back to the time of the Weimar Republic (Streeck 2004). The German form of employee participation in entrepreneurial decisions is therefore very different from other European countries where co-determination does exist, but is not nearly as well established as in Germany (Streeck 2004). The established form of co-determination in Germany, together with increasing globalisation and the associated networking, has been a fertile ground for the further development of democratic concepts of corporate governance.

An essential aspect of democratic concepts in companies is that employees participate in management decisions and have a say. In contrast, traditional management would consist of only one or at least a few people and would make decisions without involving the workforce. Traditional managers are increasingly criticised for not taking the interests of the company or the workforce as seriously as their own. Year after year, scandals occur when horrendous bonuses are paid even though the performance rendered is unclear (e.g.: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2020). The indignation of employees who were unable to participate in the distribution of bonuses is regularly reflected in the media. And the damage to the image of the organisation concerned is sometimes not sufficiently taken into account. If the financially overpaid manager has received his bonus, he only has to wait until the next scandal involving another company directs the press coverage to other events. It goes without saying that this is a very short-term idea and alternatives are needed.

In addition to such negative examples, which undoubtedly still exist in everyday business life, more and more companies are shifting their focus to a different, more philanthropic corporate culture. They start from democratic concepts and slowly open their structures and processes for participation. Or they are already extremely democratic and every person in the company can have a say in every decision. In somewhat more moderate democratic companies there are certain gradations here, so that co-determination only takes place when business decisions are of greater importance, or only that part of the employees who must be professionally qualified for a particular decision. There is increasing evidence in research and practice that employee participation leads to higher motivation through stronger ties to the company (Schmidt 2009). There are also positive influences on society, since employees who work in democratic structures show more social commitment in their private lives (Schäfer et al. 2015).

Following the division into different levels from Table 1, democracy can be thought of in conjunction with business at all three levels. At the macro level, it is macroeconomic interrelationships, at the meso level regional or urban democratic issues related to the economy, and at the micro level the individual employees of companies.

Democracy and Education

In educational science, the term democracy is used when it comes to giving children and young people the opportunity to participate in their education and upbringing. An important pioneer of this idea was John Dewey (1859-1952), who, e.g., published the book „Democracy and Education, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education 1916“ about 100 years ago. Today, the primary goal of democratic education is still to make the educational process democratic by allowing adolescents to bring their wishes and ideas into the educational process – just as adults would do. The traditional process of learning without pleasure and under pressure is now increasingly considered inhumane. The advocates of democratic education hope that democratic education will have positive effects on the development of the personalities educated in this way. Particular emphasis is placed here – to varying degrees depending on the respective author – on the development of positive self-efficacy, but also on the internalisation of democratic processes, which should ultimately lead to „democracy as a way of life“ (e.g. Pape & Kehrbaum 2019). More and more people are thus internalising democratic behaviour and living it daily and informally in all areas of life. This is expected to lead to positive social changes: Community life is developing less radically and instead more individually and more freely, leading to a better life for all (Schäfer et al. 2015).

With regard to the division into different levels from Table 1, democracy can be thought of in connection with education primarily at the micro level. E.g., individuals are given the opportunity to have a say in learning content or methods at school.

Democracy approaches entrepreneurship

Now that the focus has shifted from politics to economics and education, it is clear that the concept of democracy for this blog entry needs to be narrowed down. At this point, the first thing to do is to identify commonalities and make the necessary generalizations.

Despite the very different subject areas of politics, business and education, the first obvious common ground lies in the area of participative decisions. Participation in the sense of this blog entry is developed and firmly anchored in the culture of the organisation. It is possible that democratic processes take longer than simple top-down decisions, but on the other hand, the employees also stand behind the decisions made together.

Secondly, the possibility of participative decisions is inextricably linked to the obligation of co-responsibility. The consequences of an action are almost naturally weighed up beforehand if the consequences have to be borne by everyone, and it seems only logical that it is easier to bear negative consequences if one was involved in the decision beforehand.

The third important aspect is sharing of profits. What is meant, for example, is financial participation in the success of the company. Not only should the negative consequences be shared, but also the positive results.

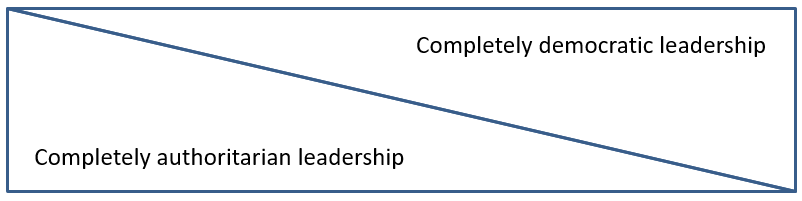

An organization that combines all three aspects can be classified – depending on the characteristics of the individual aspects – in the following figure. It assumes that all three individual aspects of participative decisions, co-responsibility and sharing of profits are either together low, medium or high. Organizational democracy defined in this way can therefore be very different: The following continuum results (a similar continuum is found here, for example, as the continuum of leadership: Tannenbaum, Schmidt 1973):

In summary, the following characteristics result in this developed continuum: Completely authoritarian leadership: aspects of participation are not provided for and the number of employees involved in decision-making is close to zero. Completely democratic leadership: In this form of organisation, participative decisions, co-responsibility and sharing of profits are balanced. Democratic concepts are further developed with the involvement of a large number of employees.

For the purposes of further analysis, democracy is thus defined as a high degree of participative decisions, co-responsibility and sharing of profits in an organisation with institutionalised democratic procedures. The other extreme is described as fully authoritarian. Of course, there are countless gradations between these two extremes, but they are not discussed in detail.

Having explained the democratic aspect in detail for this blog entry, the focus now turns to entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship!

The concept of entrepreneurship is also defined very differently – as we have already seen for the concept of democracy. This is also due to the fact that it is an interdisciplinary field of research comprising business administration, economics, geography, sociology and psychology as well as law. Very often people look to Sillicon Valley and its role models when it comes to founding a company that was very successful and now has thousands of employees. But entrepreneurship is not just Sillicon Valley, it is a very heterogeneous area (Welter, Baker, Audretsch & Gartner 2016), and moreover, it is culture-bound which means that experiences from the US cannot simply be transferred to other cultural settings. Often, entrepreneurship is specifically about the process of founding a company, i.e. a good idea leading to a start-up, self-employment and, of course, how this can be implemented as successfully as possible (e.g. Draebye 2019). However, it can also be about mere entrepreneurial behaviour of individuals who, e.g., only take advantage of price differences and buy a product in bulk packages, in which it is cheaper per piece than buying it individually. It is then sold as individual packaging to friends and acquaintances.The difference between the buying and selling price, the so-called arbitrage, remains as profit (Varian 2016). Entrepreneurship is also about starting your own business with a skill or idea, so that you finally no longer have the organizational constraints of a company and are now „your own boss“ (Beverly 2020). However, the freedom of self-employment is counterbalanced by the necessities of the company founded: possibly constant availability, a considerable workload, and of course the risk of failure, which can mean financial ruin (e.g.: Geißler 2009)! In some publications, the entrepreneur is also described as a dazzling personality who casts a spell on others and tries to explain their entrepreneurial success (e.g.: Gruber 2020).

No wonder, then, that entire courses of study deal comprehensively with entrepreneurship and degrees such as the Master of Science „Entrepreneurship and SME Management“ (SME = small and medium-sized enterprises) (University of Siegen 2019; University of Siegen 2015). Chairs at universities focus their research on the field of „entrepreneurship“ (University of Siegen 2016). Interested parties can, for example, use the „Gründungsradar“ to find out which universities offer specialisations in the field of „Entrepreneurship“ and which of these are considered particularly successful (Für-Gründer.de GmbH 2015). Support is not only available from research and theory. Specialised advice centres offer practical support in the start-up process and in the „jungle of applications“ (e.g.: Chamber of Industry and Commerce). Funding programmes are advertised (e.g.: Federal Ministry of Economics and Energy) and an unmanageable mass of management consultants advertise that they have the best tips for successful start-ups and successful founders (e.g.: four-quarters EXIST GmbH). There are also start-up offices at universities where interested students can get practical support (e.g.: University of Siegen, Gründerbüro). The list of information and support possibilities could be extended as desired.

At the same time, however, the question also arises as to what happens to founders who, without appropriate „start-up“ training, nevertheless set up companies that are successful in the long term; for example, Marc Zuckerberg founded the now globally extremely successful company Facebook in his second year of studies, even though he dropped out of his studies (Lashinsky 2016). This raises the quite legitimate question of to what extent a successful start-up is a question of training and formalities and to what extent it is a question of luck. But if happiness as a whole is crucial to success, what use are all the official support programs, courses and consulting services?

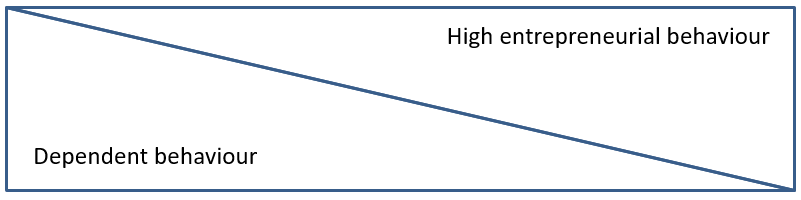

Entrepreneurship approaches democracy

From the above definition of entrepreneurship it can be deduced that it is subject to a continuum between entrepreneurial behaviour at a high level and such at a low level. The following figure shows these extremes:

In this continuum, only the two extremes will be considered in the further investigation. Dependent behaviour: In this form, there is non-entrepreneurial behavior. People usually behave as dependent employees. The share of entrepreneurial behaviour in people’s overall behaviour is very small. High entrepreneurial behaviour: In this form people have no or hardly any jobs from a secure employment relationship; they pursue their entrepreneurial behaviour completely or almost completely. Of course, there are countless gradations between these two extremes, but for reasons of space they will not be considered further here.

Democracy and entrepreneurship have now been described in detail. The next step is to merge and derive a model by combining the maximum points.

Democratic! Entrepreneurship!

At this point, the promise made at the beginning of the blog entry is fulfilled, according to which a connection between democracy and entrepreneurship would be established. Let us recall briefly that both concepts are subject to a continuum, whose respective extreme points are considered, and that we are at the micro level, where we are dealing with individual organisations and their members, and consider the result in a four-field matrix:

Dependent behaviour and low democracy lead to the field „autocracy„. Here there are no opportunities for co-determination, but a strictly hierarchical system. There is no such thing as entrepreneurial behaviour.

The combination of high entrepreneurial behaviour and autocracy leads to the field „authoritarian entrepreneurship„. Here there are no opportunities for co-determination, but high levels of entrepreneurial behaviour. This can only work in individual cases where the decisions taken are absolutely coherent with those of the management.

The combination of non-entrepreneurial behaviour and high democracy leads into the field of „laissez-faire democracy„. There is very little entrepreneurial behaviour, but there are very distinct opportunities for participation. In exceptional cases this can work. More likely, however, is a lot of participation and constant consultation without concrete results.

The combination of high entrepreneurial behaviour and high democracy leads into the field of „democratic entrepreneurship“ and readers will find the answer to the title of the blog entry in this field. Pronounced participation opportunities and strong entrepreneurial behaviour allow for a balanced relationship between participation and entrepreneurship.

Implications

The implications for the reader depend on his or her goals and on the organization he or she is working for democracy and entrepreneurship. Since the concept of democracy has been discussed here for the areas of politics, economics and education, the model can be applied primarily to organisations of this kind; however, other areas of organisation are also conceivable.

The four field matrix offers a wide range of possibilities for practice; selected examples are:

Founders who are planning to set up an organisation can use the matrix to develop and set goals. If it is to be a very autocratic/democratic enterprise, correspondingly few/many possibilities of decision participation need to be installed.

Even already existing organisations can be examined after their foundation and the desired degree of democracy and entrepreneurship can be readjusted. For example, if there is protest because profits were distributed without employee participation, the matrix can help to find ways with more participation. If there is a low level of employee commitment to the organisation, increased participation in decision-making can help to deepen it.

All these questions also affect the image stakeholders have of the company. In the global competition for talent, for example, it makes sense to be clear which applicants should be approached and to present the characteristics of democracy and entrepreneurship in a transparent manner for this target group.

Last but not least, the theory can be further developed: by studying practical cases and by further research in the field of „democratic entrepreneurship“.

Résumé

In summary, this blog entry highlights an aspect of modern entrepreneurship research that does not already exist intuitively: a connection between the concepts of democracy and entrepreneurship. Both terms are derived, classified and linked to each other with the help of a matrix. This matrix can support to examine existing organisations or those to be founded for their democratic characteristics and – if necessary – to initiate desired changes.

With the changing understanding of values, the ideas of how organisations should be also change. One of the drivers of this change is Generation Z (Scholz 2014) of those born after 1990, which are currently entering the labour market and are changing it considerably due to their completely different understanding of values. To call this generation „lazy“ is simply a too short term (Dörrenbacher 2019). It tends to be more uncompromising, represents its interests more intensively and infects other generations with its changed views (Ehrhardt 2019).

Taking these findings into account as an entrepreneur, democratic entrepreneurship can be a reasonable and modern way to arouse the interest of these people and to find sufficiently qualified personnel in the future.

References

Bergmann, Frithjof, Neue Arbeit, Neue Kultur, Freiamt (Arbor) 2004.

Bergmann, Gustav/Daub, Jürgen/Özdemir, Feriha, Editorial: Demokratie in der Wirtschaft? In: Wirtschaft demokratisch, Teilhabe, Mitwirkung, Verantwortung, Göttingen (Vandenhöck & Ruprech) 2019, 11-26, 21.

Beverly, Harlan T., Navigating Your Way to Startup Success, Boston/Berlin (Walter de Gruyter) 2018, 8.

Bundestag, Demokratie, https://www.bundestag.de/services/glossar/glossar/D/demokratie-245374, undated, last downloaded 23.01.2020.

Bundesverfassungsgericht, No prohibition of the National Democratic Party of Germany as there are no indications that it will succeed in achieving its anti-constitutional aims, https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2017/bvg17-004.html, 17.01.2017, last downloaded 12.05.2020.

Chamber of Industry and Commerce, Existenzgründung und Unternehmensförderung, https://www.ihk.de/existenzgruendung-und-unternehmensfoerderung, undated, last downloaded 17.05.2020

Dewey, John, Democracy and Education, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, New York (Macmillan Company) 1916.

Dörrenbächer, Sven, Generation Z – faul, desinteressiert, Smartphone-süchtig? https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/bilanz/article195118767/Falsch-verstanden-Generation-Z-faul-desinteressiert-Smartphone-suechtig.html, 13.06.2019, last downloaded 14.05.2020.

Draebye, Mikkel, Start-Up Entrepreneuship, The smart way, Milano (Bocconi University Press) 2019.

Ehrhardt, Mischa, Eigene Wertevorstellungen – Mischt die Generation Z die Arbeitswelt auf? https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/heute/mischt-die-generation-z-die-arbeitswelt-auf-100.html, 13.07.2019, last downloaded 14.05.2020.

Federal Ministry of Economics and Energy, Existenzgründung – Motor für Wachstum und Wettbewerb, https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Dossier/existenzgruendung.html, undated, last downloaded 23.01.2020.

four-quarters EXIST GmbH, https://www.gründungsberater.com/, undated, last downloaded 17.05.2020

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Dieselskandal: Landgericht äußert Zweifel an Anklagepunkten gegen Winterkorn, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/unternehmen/dieselskandal-zweifel-an-anklage-gegen-winterkorn-16586455.html, 17.01.2020, last downloaded 13.05.2020.

Für-Gründer.de GmbH, Entrepreneurship studieren: Für wen ist das geeignet? Hochschulen mit Vorbildcharakter in der Gründungsförderung, Figure 14, https://www.fuer-gruender.de/blog/entrepreneurship-studieren/, 08.07.2015, last downloaded 23.01.2020.

Geißler, Cornelia, Entrepreneure? In: https://www.harvardbusinessmanager.de/heft/artikel/a-638727.html, Heft 08/2009, last downloaded 07.02.2020.

Gruber, Marc, Was ist entrepreneurship? In: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/start-up-was-ist-entrepreneurship-159417.html, 23.05.2020, last downloaded 07.02.2020.

Kuhn, Axel, Die Französische Revolution, in: Henke-Bockschatz, Gerhard (Hrsg.), Die französische Revolution, Kompaktwissen Geschichte, Stuttgart (Reclam) 2018, 10-11.

Lashinsky, Adam, Mark Zuckerberg, Fortune, 12/1/2016, Vol. 174 Issue 7, p66-72.

Mehr Demokratie e.V., https://www.mehr-demokratie.de/english/, undated, last downloaded 23.01.2020.

Pape Helmut/Kehrbaum Tom: John Dewey. Über Bildung, Gewerkschaften und die demokratische Lebensform, in: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Study, Nr. 421, Düsseldorf (Hans Böckler Stiftung) 2019, 77.

Robertson, Brian J., Holacracy: The Revolutionary Management System that Abolishes Hierarchy, New York (Penguin) 2015.

Schäfer, Mechthild/Sandfuchs, Uwe/Daschner, Peter/Schubart, Wilfried, Handbuch Aggression, Gewalt und Kriminalität bei Kindern und Jugendlichen, Bad Heilbrunn (Julius Klinkhardt) 2015, 460.

Schmidt, Birgit E., Vom Schatten herrschender Verhältnisse oder: Was fördert Organisationales Commitment? In: Journal Psychologie des Alltagshandelns / Psychology of Everyday Activity, Vol. 2 / No. 2, ISSN 1998-9970, 2009, 22-32, 30.

Scholz, Christian, Generation Z: wie sie tickt, was sie verändert und warum sie uns alle ansteckt, Weinheim (Wiley VcH) 2014.

Streeck, Wolfgang, Mitbestimmung, unternehmerische, in: Schreyögg, Georg/Werder, Axel, Handwörterbuch Unternehmensführung und Organisation, Stuttgart (Schäffer-Pöschel) 2004, S. 880-887.

Tannenbaum, Robert/ Schmidt , Warren H.: How to Choose a Leadership Pattern. In: Harvard Business Review 36/1958. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1973, S. 162–180, 164, last downloaded 06.02.2020.

University of Siegen, https://www.wiwi.uni-siegen.de/business-studieren/master/master-sbm.html?lang=de, 11.08.2015, last downloaded 27.01.2020.

University of Siegen, https://www.wiwi.uni-siegen.de/welter/, 08.01.2016, last downloaded 27.01.2020.

University of Siegen, https://www.uni-siegen.de/zsb/studienangebot/master/sme.html, 17.12.2019, last downloaded 27.01.2020.

University of Siegen, Gründerbüro, https://www.gruenden.uni-siegen.de/, undated, last downloaded 23.01.2020.

Varian, Hal, Grundzüge der Mikroökonomik, Oldenburg (De Gruyter) 2016, 225-226.

Vorländer, Hans, Demokratie: Geschichte, Formen, Theorien, München (Beck) 2003.

Welter, Friederike/Baker, Ted/Audretsch, David B./Gartner, William, Everyday Entrepreneurship – A Call for Entrepreneurship Research to Embrace Entrepreneurial Diversity, in: Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, October 2016, 1-11, 2-3, 8.