Natalia Tsatsenko, University of Siegen

Abstract

Over the last decades, the contribution of entrepreneurship to economic growth is broadly recognized. Due to the fact that institutions may shape conditions for the development of entrepreneurship or destroy it, I (institution) is included as a third variable in the relationship between E (entrepreneurship) and EG (economic growth). This discussion consists of two blog entries prepared by Natalia Tsatsenko and Ganira Ibrahimova.

The first blog is called “Entrepreneurship measurement in recent studies: What can we learn?” The purpose of this blog is to describe the main data sources concerning entrepreneurship under the cross-country level and to provide the reader with an insight into the multi-dimensional concept of entrepreneurship. Moreover, the key groups of dichotomous of entrepreneurship such as formal and informal, legal and illegal, necessity and opportunity are highlighted in detail. This blog focuses on two multi cross data sources like the World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey (WBGES) and the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (GEM) and draws attention to the following aspects as methodology, the main indicators, and existed limitations. We show that the classification of entrepreneurship is partly reflected in both data sources so that it supports the statement about the diverse aspects of entrepreneurship and its complexity of the measurement.

The second blog is called “How institutions affect our economic behavior”

The purpose of the second blog entry is to show the relationship between institutions and economic agents‘ behavior. It provides the actual definition of institutions, general understanding of its classification (formal and informal institutions), and then, depicts the impact of institutions on economic behavior in the context of entrepreneurship through different case study analysis.

Since the topic “Institutions-Entrepreneurship-Economic Growth” is very trendy nowadays and located at the intersection of independent research areas, and due to the complexity and rapid dynamics of it, in these blogs, we make an attempt to provide readers with some core aspects of this subject.

Part 1: Entrepreneurship Measurement in Recent Studies: What can we learn about it? – Blog Entry prepared by Natalia Tsatsenko (below)

Part 2: How institutions affect our economic behavior? – Blog Entry prepared by Ganira Ibrahimova

Entrepreneurship is a multi-dimensional concept. What should we know about it?

The starting point is that entrepreneurship is a complex phenomenon. The discussion goes on about it. Moreover, polemics about the issue as “How should we interpret the multi-dimensional concept of entrepreneurship” will keep generating new ideas and assumptions in the future. One could argue that entrepreneurship expresses differently so that it influences on measurement issues. Notwithstanding, the academic society accepts several definitions which lead to various indicators, we should employ it carefully into our research due to differences between national statistical offices. Although there are well-known and good established international entrepreneurship data, there is still room for further improvements. In this blog entry, the goal is to describe the main data sources about entrepreneurship under the cross-country level and show that methodologies of these data sources are still in the process. One could add that it looks like the permanent process of growth that depended on the exogenous and endogenous factors.

An important point is to consider a couple of illustrations about the multi-dimensional concept of entrepreneurship and why it is. For example, Acs et al. (2009) stress that entrepreneurship is “a broad term with many different meanings”. According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor project 2014 (which is presented the cross-countries data about entrepreneurship), the notion as entrepreneurship has many faces that could comprise initiatives with high ambitious business activities but also that are accompanied by less ambitious. To investigate the relationship between entrepreneurship and institutions, between entrepreneurship and economic development, entrepreneurship, and economic growth, it needs to provide an overview of the definition of “entrepreneurship”.

It should be highlighted the main common definition of entrepreneurship is formulated by the Green Paper Entrepreneurship in Europe (published by European Commission in 2003): entrepreneurship is characterized by “the mindset and process to build and develop economic activity by blending risk-taking, creativity and/or innovation with sound management, inside a new or an existing organization”.

Note that the emergence of a new direction in the field of modern entrepreneurship is directly related to the establishment and formulation of new definitions. For instance, Terjesen et al (2016) use the term “comparative international entrepreneurship”. It could be interpreted as “the cross-national comparisons of domestic entrepreneurship”. Thus, the challenges in determine entrepreneurship leads to the difficulty of doing the measurement, particularly at the cross-national level.

Categories of Entrepreneurship

In this sub-section, we review the main group of dichotomous about entrepreneurship such as formal and informal, legal and illegal, necessity, and opportunity.

Firstly, in the case of formal and informal entrepreneurship, the registration status of a firm is the main indicator of the formal entity. That means the firm has been registered with the appropriate government agency and then the firm is authorized to do business. Formal firms are related to taxable sectors. However, the categorization of a firm as “formal” or “informal” does not determine any indication of the legality or not of their business activities. It has been found that in many developing countries motivation for entrepreneurs, especially in small scale enterprises, engages in the formal sector can be weak due to high taxes (Desai, 2011). According to ILO Report (2015), a high incidence of enterprise informality is related to several negative aspects such as low productivity, a poor tax base, unfair competition, and unreliable working conditions. It is assumed that in some developing countries informal SMEs outnumber formal enterprises of the same size.

Secondly, legal and illegal entrepreneurship as the dichotomy is connected to interchangeably with the formal/informal dichotomy, but they are not the same. Furthermore, legal firms are involved in legal activities that are permitted by law. Alternatively, illegal entrepreneurs are named entrepreneurs who deal with illegal activities that depend on the explicit legal code and regulatory frameworks in the country (Desai, 2011).

Thirdly, the motivation for entrepreneurial activities and to be entrepreneurs derives from two groups of entrepreneurship such as necessity and opportunity. Now it is important to understand the distinction between both groups. Necessity-driven entrepreneurs are related to the three main aspects such as limited employment options, weak social security systems, and a high rate of self-employed among populations (Lundström, A., & Stevenson, L. A., 2005). Furthermore, there is a connection between necessity entrepreneurship and the informal sector. Based on the paper by Desai (2011), in developing countries, high rates of necessity entrepreneurship can be stemmed by the size of the informal sector. All in all, necessity entrepreneurs are an important force in the economy of developing countries to avoid unemployment. By contrast, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are individuals who search a way to earn more money, and their motives to be entrepreneurs are “less dependent on the economic environment” based on the GEM framework (GEM, 2014). Additionally, Desai (2011) underlines opportunity entrepreneurship is associated with the advantages of doing entrepreneurial activities. In other words, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs made a choice to be entrepreneurs after considering several job alternatives. To summarize, this dichotomous (necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship) is different from social-economic characteristics.

Having described types of entrepreneurship, we could suggest three dichotomous are more or less connected with each other. So far, we have discussed the heterogeneous nature of entrepreneurship. Further, we will highlight that the data sources of entrepreneurship support the idea of entrepreneurship dichotomous. For example, the GEM report focuses on necessity and opportunity indicators.

Measurement of Entrepreneurship: Sources and Indicators

In this section, we describe the existing data sources for cross-country comparison and main indicators for measuring entrepreneurship. The starting point of our discussion about measurements of entrepreneurship is the book of “Empirical analysis of entrepreneurship and economic growth” written by Van Stel (2006) where he represents four approaches. Firstly, entrepreneurship could be reckoned by means of a number of self-employment and business owner. Secondly, it is the degree of market entry. Particularly, researchers are interested to know the number of new start-up firms. Thirdly, entrepreneurship could be described as the process of beginning a new business. It means entrepreneurial activities. This approach is based on the dataset of the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (GEM) which will be considered more detailed later. Fourthly, the idea that the proportion of small firms in the total amount of shipment of an economy. All in all, Van Stel (2006) states that the main idea is that entrepreneurship is a very broad concept. It could not be measured through only one indicator.

Different data sources on entrepreneurship could lead to contradictory findings due to country-specific differences and the diversity of data to measure “entrepreneurship”. As stated by Acs et al (2008), it is necessary to get understanding what preciously the data indicate and determine and also “what element of entrepreneurial dynamics is being measured”.

The problem of measurement entrepreneurship across countries is recognized by many researchers (Desai, 2011; Urbano et al, 2019; A´lvarez et al, 2014; Terjesen et al, 2016; Klapper, 2006).

The Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (GEM)

The Global Entrepreneurial Monitor project opened a completely new way to the problem connected to measure entrepreneurship and reflect the multidimensional characteristics of entrepreneurial dynamics. The project was launched in 1997 by Michel Hay and Bill Bygrave (Acs et al. 2009) and then the first study was performed in 1999 including ten developed countries under the guidance Paul Reynolds. Twenty-one years later, the project continues to evolve and is a key data source for multi-country studied. Nowadays the GEM project brings together researchers from all over the world and the number of countries varies from year to year. For example, in 2013 more than 3,800 country experts on entrepreneurship issues were involved to conduct the study across 70 national economies. As mentioned in the anniversary issue in 2013 in which the GEM project celebrated fifteen years of estimating entrepreneurship dynamics across the globe, more than 104 countries have been investigated.

Note that the GEM project is unique of nature because it explores the dynamics of the level of entrepreneurial activity in the various countries and how it connects to the level of economic development and therefore identifies factors that stimulate or impede entrepreneurial activity. Moreover, the GEM determines the extent to which entrepreneurial activities influences economic growth in terms of specific economies such as factor-driven, efficiency-driven, and innovation-driven (Survey GEM, 2016).

We should mention that the key goal of GEM is to try to explain why rates of entrepreneurship “differ among economies at similar stages of economic development” (GEM 2014).

GEM Methodology: Key issues

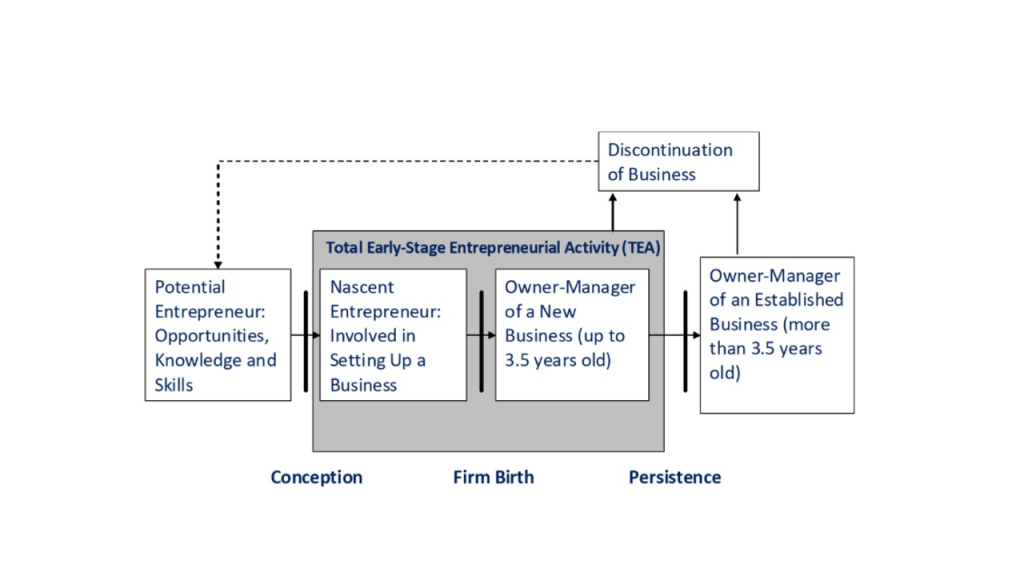

As we have already discussed entrepreneurship is the process. This keyword “process” is “the first stone” to build and establish the GEM methodology. Hence, based on the GEM methodology there are several phases such as potential entrepreneurs, nascent entrepreneurs, new business owners, established business owners (see Figure 1).

To better understand Figure 1, we consider step by step all phases and highlight the main terminologies concerning the entrepreneurship process under the GEM.

- Potential entrepreneurs are who still only expecting to start in the near future.

- The Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA): The key indicator of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor is the Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) which consists of nascent entrepreneurs and new business owners. More detail, the TEA rate shows the percentage of the adult population from 18 to 64 years who have taken steps to start a new business (nascent entrepreneurs) or who have run new businesses and paid salaries over 3 months and less than 42 months (new entrepreneurs) (GEM, 2016). In this line, we should give the common definitions concerning two elements of the TEA.

- The nascent entrepreneurs are people actively involved in starting a new venture but do not pay salaries or wages for the period more than three months (Acs et al. 2008, p.279, the GEM 2016 p. 21).

- New business owners are people who have moved beyond the nascent stage and have paid salaries and wages for more than three months but less than 42 months.

- Established business owners are individuals who run ventures for more than three and a half years.

Under the GEM conceptual framework entrepreneurial activities are presented by three groups as the following:

- Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA).

- Established business ownership rate is the percentage of the adult population who are accounted as established business owners.

- Business discontinuation rate is the percentage of the adult population aged between 18 and 64 years (who are either a nascent entrepreneur or an owner-manager of a new business) who have, in the past 12 months, discontinued a business, either by selling, shutting down, or otherwise discontinuing an owner/management relationship with the business (GEM, 2016).

It is important to stress that the GEM shows that an economy could have a large number of potential and nascent entrepreneurs, but this amount will not be transformed directly to a high number of established firms that will be sustainable for a long time. As already mentioned, the TEA rate includes nascent entrepreneurs. It is expected that TEA rates are usually high in emerging economies but established business ownership rate is usually low (GEM, 2013).

The World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey (WBGES)

The Enterprise Surveys that have been published by the World Bank since 2002 cover all geographic regions and account firms of different sizes, namely small, medium, and large. WBGES is a unique dataset in relation to firm data across countries. A representative sample of firms is derived from the non-agricultural formal private economy. Note that Enterprise Surveys consists of 12 topics such as corruption, firm characteristics, innovation, technology, performance and etc. (World Bank Group, Survey Methodology, 2019).

The main indicator of entrepreneurship is the entry rate that is defined as new firms (those that were registered in the current year) as a percentage of total registered firms. Another important indicator is the business density which is determined by the number of registered firms as a percentage of the active population, (Klapper, 2006).

It should be mentioned a limitation of this dataset. The WBGES does not include firms from the informal sector. That means that a number of new officially registered limited liabilities corporations are only accounted for it. In spite of some limitations of GEM and WBGES, both data sources are highly accepted by the academic community to discover modern entrepreneurship.

What does the scientific literature say about source data and their applicability?

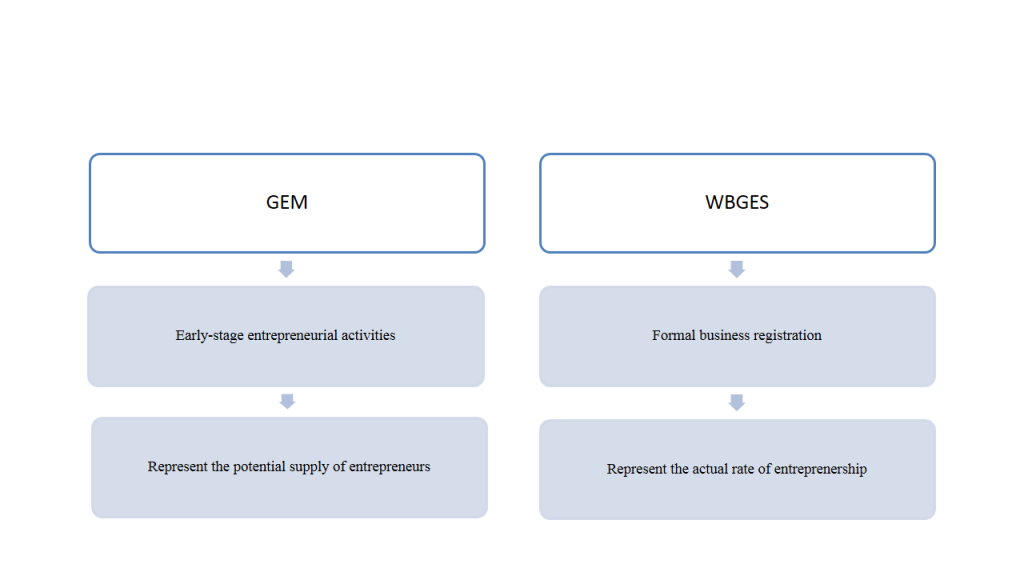

In the paper Acs et al. (2008) with the title “What does “entrepreneurship” data really show?” researchers compare two popular sources for internationally comparable data, namely the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and the World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey. Summarizing their findings, Figure 2 demonstrates the main discrepancy between two datasets.

The main point is that the data sets measure entrepreneurship dynamics in different ways. GEM takes into account entrepreneurial intentions. The World Bank’s Entrepreneurship Survey reflects only the actual level of entrepreneurial activity.

Note that in the paper by Acs et al. (2009), scholars show us how the GEM project has evolved in the first years since its emergence. In this research work we can learn that what means “appropriate measure” of entrepreneurship and how the GEM project could have been designed and developed. Important finding is that new measurement aspects or new data will open up possibilities for entirely new research questions. Another supporting argument could be taken from the article by Terjeusen et al. (2016), the potential future direction of research is data on the existence of unexplored countries. Another supporting argument could be taken from the paper by Terjesen et al. (2016), potential future direction of research is the existence data of unstudied countries.

To sum it up, the discussion about the diversity between existed measures due to “fundamentally different manifestations of entrepreneurship” we have found in the paper by Desai (2011). The modern research on entrepreneurship depends on measurements and their interpretations. For example, Desai (2011) proposes that it will be growing interest in differentiating between types of entrepreneurship being measured, on the one side, and it needs to continue to improve the system of entrepreneurship measurement for international comparison, on the other side. In line with Acs et al., Desai (2011) underlines firm formation and firm registration are not equal and one may not necessarily transform into another.

Conclusion

Having considered the evolving views of the issues concerning entrepreneurship measurement, we show the measurement system of entrepreneurship has been changed under the dynamics of this research direction. Moreover, we get an insight into recent research works on this topic, particularly on more complex data sources in the context of cross-country level. As stated by Urbano et al. (2019), there are two main ways to analyze the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth either focus on “the determinants” which foster entrepreneurial activity or to study “the effect of new business creation”. In both cases, institutions are the core variables which integrated in this relationship like I (institutions) =>E (entrepreneurship) => EG (economic growth). Hence we could not neglect institutional factors if we study the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth. However, it is not that simple. Further, one may put the following questions: “What type of institutions (formal or informal) affects entrepreneurship? What do we mean when we talk about the formal institutional factors in the context of the entrepreneurship field? How institutions affect our decisions if we are entrepreneurs?” This group of questions is discussed in the blog entry prepared by Ganira Ibrahimova. The reader can learn from case-studies how institutions immediately influence on our economic behavior. All in all, it will be interesting to get an insight into recent research works on this topic.

References

Acs, Z. J., Amorós, J. E., Bosma, N. S., & Levie, J. (2009). From entrepreneurship to economic development: Celebrating ten years of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 29(16), 1-15.

Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476-494. doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Klapper L. F. (2008) What does „entrepreneurship” data really show? Small business economics, 31, 265 – 281. doi 10.1007/sl 1187-008-9137-7

Álvarez, C., Urbano, D., & Amorós, J. E. (2014). GEM research: achievements and challenges. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 445-465. doi 10.1007/s11187-013-9517-5

Desai, S. (2011). Measuring entrepreneurship in developing countries. In Entrepreneurship and economic development (pp. 94-107). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

GEM (2014) Global Entrepreneurship monitor 2013 Global Report Fifteen Years of Assessing Entrepreneurship Across the Globe by Amorós, J.E. & Bosma N. Retrieved from: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report.

GEM (2016) The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report 2016/2017. Retrieved from: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report.

GEM (2019) How GEM defines entrepreneurship. Retrieved from: https://www.gemconsortium.org/wiki/1149 .

Green Paper Entrepreneurship in Europe (2003) by European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/green-paper-entrepreneurship-europe-0_en.

2015. Small and medium-sized enterprises and decent and productive employment creation. International Labour Conference, 104th Session. Report IV: Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_358294.pdf .

Klapper, L. (2006). Entrepreneurship: how much does the business environment matter?. Viewpoint series, Note, 313.

Lundström, A., & Stevenson, L. A., (2005) Entrepreneurship Policy: Theory and Practice, Springer Science & Business Media.

Terjesen, S., Hessels, J., & Li, D. (2016). Comparative international entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 42(1), 299-344. doi: 10.1177/0149206313486259

Urbano, D., Aparicio, S., & Audretsch, D. (2019). Twenty-five years of research on institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: what has been learned?. Small Business Economics, 53(1), 21-49. doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0038-0

World Bank Group (2019) World Bank Group, Survey Methodology. Retrieved from: https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/methodology .